Ο

καθρέφτης του υπνοδωματίου, όπου ο Βαν Γκογκ είδε τον εαυτό του να

κόβει το αυτί του, εμφανίζεται σε αυτόν τον πίνακα του 1889.

Ένα ζωντανό αντίγραφο του διάσημου αυτιού του Βαν Γκογκ σε γερμανικό μουσείο το 2014.

Vincent van Gogh Cut Off His Ear to Silence Hallucinations and 10 Other Things We Learned in a New Book About Him

Ο Βίνσεντ βαν Γκογκ έκοψε το αυτί του για να σταματήσει τις παραισθήσεις του και άλλα δέκα πράγματα που μάθαμε σε ένα νέο βιβλίο για αυτόν

Sarah Cascone,

September 27, 2018

No one can deny the artistic genius of Dutch Post-Impressionist artist Vincent van Gogh,

whose masterworks are among the most famous and easily recognizable

paintings in the world. Nevertheless, the artist’s reputation remains

inextricably tied to his struggles with mental illness—this is, after

all, the man who cut off his left ear and gifted it to a female acquaintance.

It was that infamously violent incident in Arles, France, on December 23, 1888, that led Van Gogh to Saint-Paul-De-Mausole, an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France. He lived there for just over a year, from May 8, 1889, to May 16, 1890. In the new book Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, journalist and Van Gogh scholar Martin Bailey delves into this critical and remarkably fruitful period in the artist’s career. The author brings to light new details about what life at Saint-Paul was like, the paintings Van Gogh created while he was there, as well as insight into the artist’s fragile mental state, and a fascinating account of the staff and the other patients.

To illuminate this history, Bailey’s gorgeously illustrated tome draws on primary sources, including Van Gogh’s letters, an unpublished diary from a local artist who knew Van Gogh at the time, and rarely consulted records from the municipal archives of Saint-Rémy, of Saint-Paul’s admission register from the late 19th century.

The author also considers the history of the facility, which was founded by Louis Mercurin as an impressively progressive institution that embraced music and art as forms of therapy. The asylum was given a failing grade by inspectors in 1874 and was in dire need of reform prior to Van Gogh’s arrival. Though conditions during the artist’s institutionalization still left room for improvement, Van Gogh became close with the director, Théophile Peyron, and maintained the freedom to work (save for the nadir of his mental crises).

The institutionalization was voluntary, and unlike many asylums of the time, Saint-Paul eschewed the use of straight jackets, refusing to chain up its patients or employ other cruel practices. Nevertheless, mental illness was still poorly understood at the time, and institutionalization must have been difficult for Van Gogh.

The artist, lucid for the majority of his stay, was surrounded by men

who were much worse off, according to the book. There was an elderly

priest, likely suffering from dementia, a nonverbal “idiot” with a

mental age of less than three who lived at Saint-Paul for nearly 45

years, and a man who Van Gogh complained in a letter “breaks everything

and shouts day and night.” (Bailey has identified many of these men by

name for the first time.)

Nevertheless, Van Gogh came to identify with his fellow patients, who he called “my companions in misfortune.” He also continued to struggle, suffering through four severe mental health episodes while he was there. During these periods, Van Gogh would poison himself by eating his paints, and then become paranoid, convinced that someone else was making an attempt on his life. “My memories of these bad moments are vague,” he wrote to his brother, Theo van Gogh, admitting to eating “filthy things.”

“Strictly speaking I’m not mad, for my thoughts are absolutely normal and clear between times…. but during the crises it’s terrible however, and then I lose consciousness of everything,” Van Gogh explained, noting in another missive that “it’s to be presumed that these crises will recur in the future, it is ABOMINABLE.”

There has been endless speculation over the years as to the true nature of the mysterious mental illness

that plagued Van Gogh. Like others before him, Bailey speculates might

have been bipolar disorder. Whatever the true diagnosis, toward the end

of his stay at Saint-Paul, Van Gogh came to feel that being surrounded

by the mentally ill made his own issues worse.

In between episodes—and occasionally during them—Van Gogh made great paintings, over 150 of which survive. From his bedroom window, the artist enjoyed views of golden wheatfields, which he painted throughout the year. Beyond lay the equally inspiring olive groves, and the hills of Les Alpilles. Saint-Paul itself was also a common subject for the artist, who spent many hours in its beautiful, if somewhat overgrown, walled garden, and occasionally depicted the facility’s rooms. (Only one piece, which we’ll get to later, featured the building’s exterior.)

Unsurprisingly, given his productivity, Van Gogh wasted not a minute upon arriving at Saint-Paul. The very next day, he was at work on two flower paintings, including Irises, now in the collection of Los Angeles’s J. Paul Getty Museum. It took just two weeks to almost completely exhaust the art supplies he had brought with him from Arles.

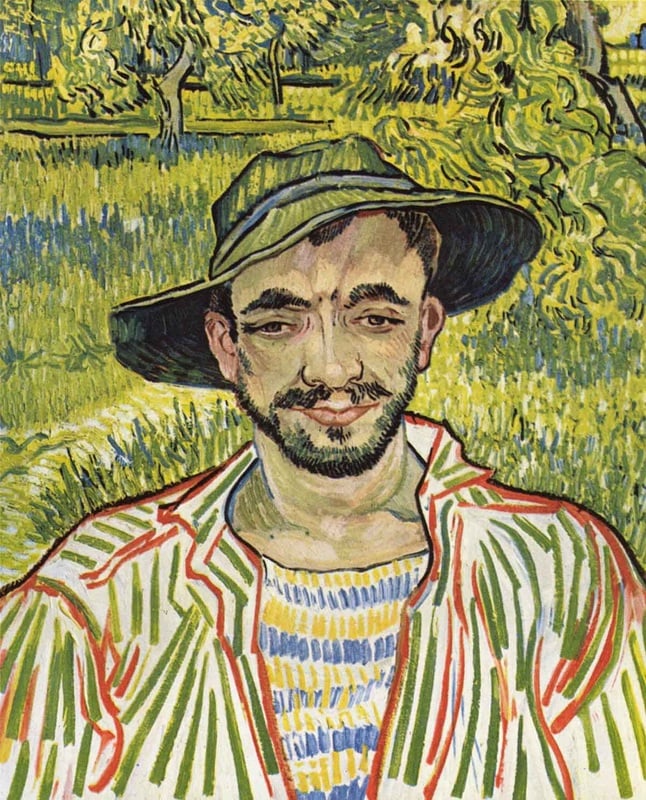

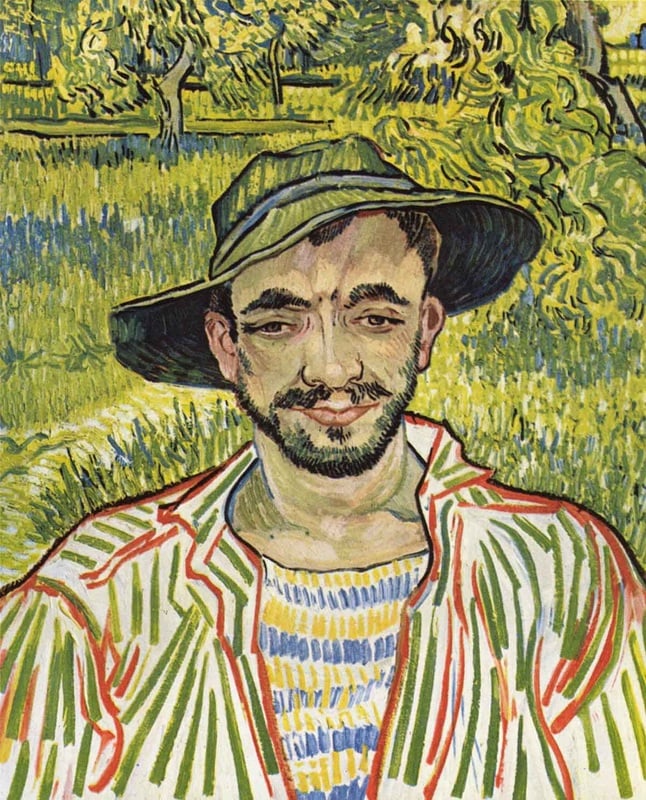

Other works completed at Saint-Paul include self-portraits and portraits of the staff. Bailey identifies Portrait of a Gardener

(1889) as farmer Jean Barral, a conclusion based on the work of a local

researcher who, in the 1980s, spoke to the grandson of an asylum

orderly—and even two of Van Gogh’s fellow patients. Van Gogh also

created oil paintings based on black and white copies of the work of

other artists, including Eugène Delacroix’s Pietà and Jean-François Millet’s series “Labours of the Fields.”

Although institutionalization did not cure what ailed Van Gogh, the artist’s time at Saint-Paul led to the creation of some of his most beloved works.

Here are 11 things we learned about Van Gogh from Bailey’s new book.

Back in 1987, Bailey had the rare opportunity to visit what was once the men’s block, since modernized, where Van Gogh would have lived during his institutionalization. According to the author, the hospital, inundated by similar requests as the centenary of the artist’s death approached, soon cracked down on such access, which is now all-but unheard of. (The book includes photographs taken by Bailey in this off-limits area, the first such images ever published in color.)

Before booking a visit, note that the hospital does not own any work by Van Gogh. The artist offered to donate some paintings to the Catholic Sisters of the Order of Saint Joseph, who ran the facility, but they found his work disturbing and turned him down. Since Van Gogh checked out in 1890, his work has only once been exhibited in the town of Saint-Rémy, back in 1951.

It was that infamously violent incident in Arles, France, on December 23, 1888, that led Van Gogh to Saint-Paul-De-Mausole, an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France. He lived there for just over a year, from May 8, 1889, to May 16, 1890. In the new book Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, journalist and Van Gogh scholar Martin Bailey delves into this critical and remarkably fruitful period in the artist’s career. The author brings to light new details about what life at Saint-Paul was like, the paintings Van Gogh created while he was there, as well as insight into the artist’s fragile mental state, and a fascinating account of the staff and the other patients.

To illuminate this history, Bailey’s gorgeously illustrated tome draws on primary sources, including Van Gogh’s letters, an unpublished diary from a local artist who knew Van Gogh at the time, and rarely consulted records from the municipal archives of Saint-Rémy, of Saint-Paul’s admission register from the late 19th century.

The author also considers the history of the facility, which was founded by Louis Mercurin as an impressively progressive institution that embraced music and art as forms of therapy. The asylum was given a failing grade by inspectors in 1874 and was in dire need of reform prior to Van Gogh’s arrival. Though conditions during the artist’s institutionalization still left room for improvement, Van Gogh became close with the director, Théophile Peyron, and maintained the freedom to work (save for the nadir of his mental crises).

The institutionalization was voluntary, and unlike many asylums of the time, Saint-Paul eschewed the use of straight jackets, refusing to chain up its patients or employ other cruel practices. Nevertheless, mental illness was still poorly understood at the time, and institutionalization must have been difficult for Van Gogh.

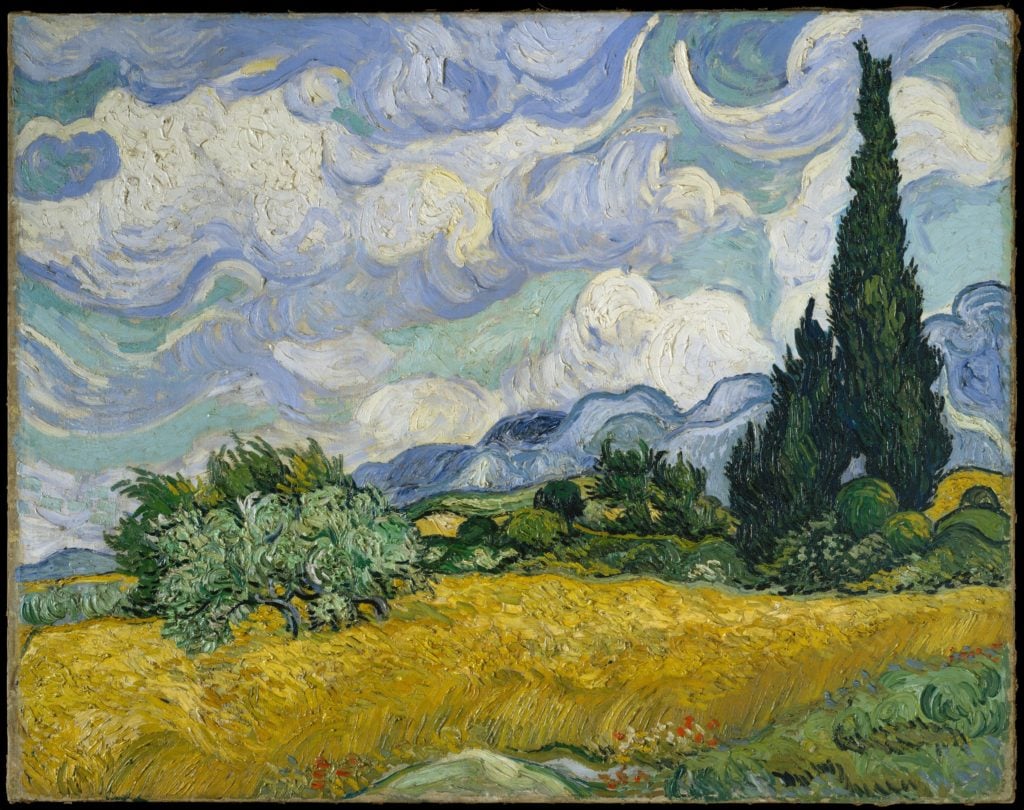

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield With Cypresses (1889). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Nevertheless, Van Gogh came to identify with his fellow patients, who he called “my companions in misfortune.” He also continued to struggle, suffering through four severe mental health episodes while he was there. During these periods, Van Gogh would poison himself by eating his paints, and then become paranoid, convinced that someone else was making an attempt on his life. “My memories of these bad moments are vague,” he wrote to his brother, Theo van Gogh, admitting to eating “filthy things.”

“Strictly speaking I’m not mad, for my thoughts are absolutely normal and clear between times…. but during the crises it’s terrible however, and then I lose consciousness of everything,” Van Gogh explained, noting in another missive that “it’s to be presumed that these crises will recur in the future, it is ABOMINABLE.”

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of a Gardener (1889), now identified as Jean Barral. Courtesy of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome.

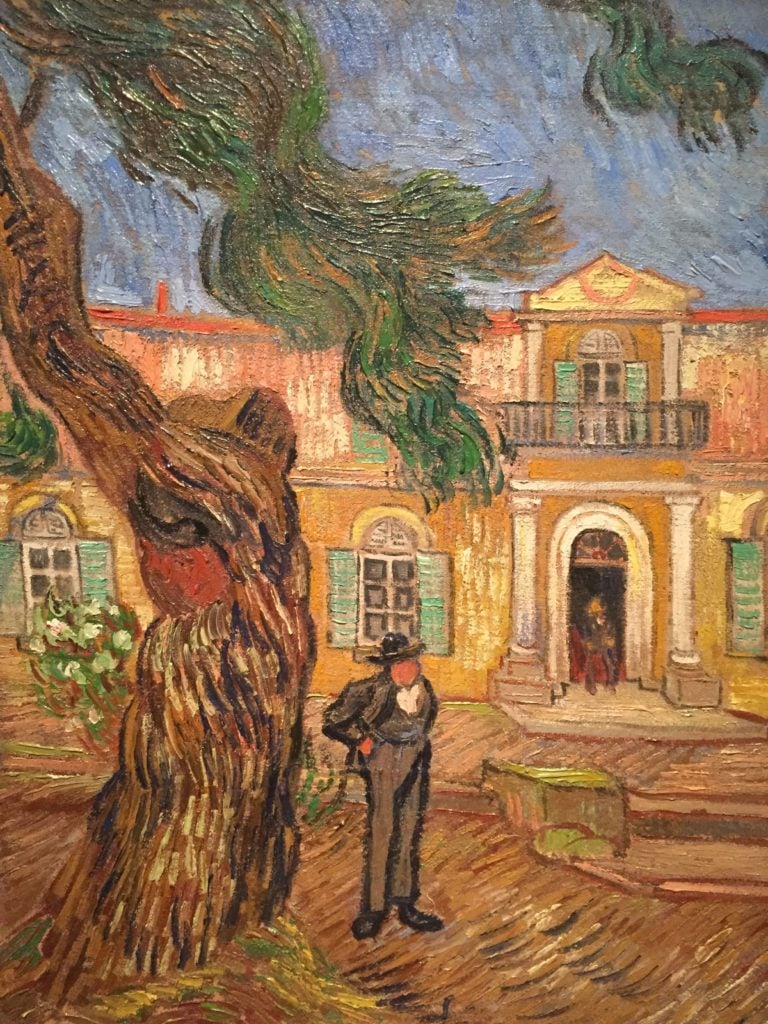

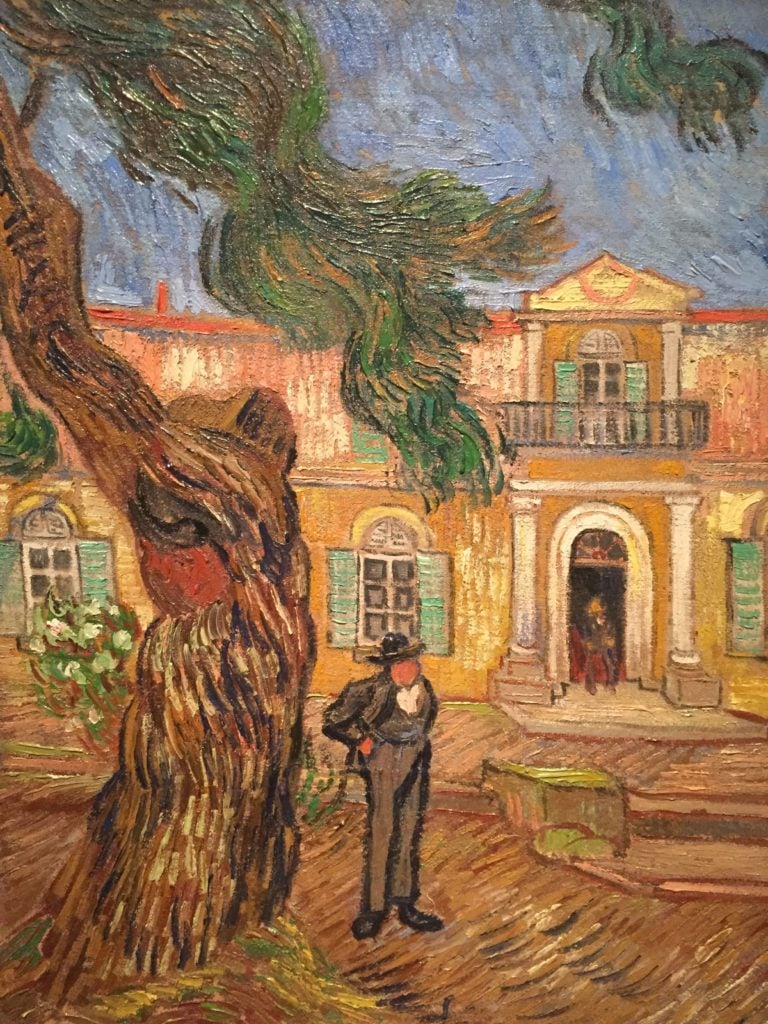

In between episodes—and occasionally during them—Van Gogh made great paintings, over 150 of which survive. From his bedroom window, the artist enjoyed views of golden wheatfields, which he painted throughout the year. Beyond lay the equally inspiring olive groves, and the hills of Les Alpilles. Saint-Paul itself was also a common subject for the artist, who spent many hours in its beautiful, if somewhat overgrown, walled garden, and occasionally depicted the facility’s rooms. (Only one piece, which we’ll get to later, featured the building’s exterior.)

Unsurprisingly, given his productivity, Van Gogh wasted not a minute upon arriving at Saint-Paul. The very next day, he was at work on two flower paintings, including Irises, now in the collection of Los Angeles’s J. Paul Getty Museum. It took just two weeks to almost completely exhaust the art supplies he had brought with him from Arles.

Vincent van Gogh, Irises (1889). Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Although institutionalization did not cure what ailed Van Gogh, the artist’s time at Saint-Paul led to the creation of some of his most beloved works.

Here are 11 things we learned about Van Gogh from Bailey’s new book.

1. You Can Visit Van Gogh’s Asylum Today (But Don’t Expect to See His Work)

Formerly a monastery, Saint-Paul-De-Mausole has become something of a tourist attraction, less for the charms of its Romanesque architecture than for its links to Van Gogh. The facility remains a psychiatric hospital today, but the public can visit the gardens, the chapel, and 12th-century cloister, as well as several rooms, including one furnished as if it were 1889 again. The sign reads “Van Gogh’s Bedroom,” but the artist actually slept in a different part of the asylum.Back in 1987, Bailey had the rare opportunity to visit what was once the men’s block, since modernized, where Van Gogh would have lived during his institutionalization. According to the author, the hospital, inundated by similar requests as the centenary of the artist’s death approached, soon cracked down on such access, which is now all-but unheard of. (The book includes photographs taken by Bailey in this off-limits area, the first such images ever published in color.)

Before booking a visit, note that the hospital does not own any work by Van Gogh. The artist offered to donate some paintings to the Catholic Sisters of the Order of Saint Joseph, who ran the facility, but they found his work disturbing and turned him down. Since Van Gogh checked out in 1890, his work has only once been exhibited in the town of Saint-Rémy, back in 1951.

Vincent van Gogh, View of the Asylum With a Pine Tree (1889). Courtesy of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

[............................]

Συνεχίστε την ανάγνωση

|

|

|

By Sarah Cascone |

|

|

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου