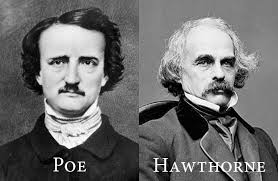

Move Over, Poe—The Real Godfather of Gothic Horror Was Nathaniel Hawthorne

The "Scarlet Letter" author's short stories are like a Puritan "Twin Peaks"

Το "Το άλικο γράμμα" από τα σύντομα διηγήματα του συγγραφέα είναι σαν μια πουριτανική εκδοχή της ταινίας Τουίν Πικς

Edgar Allan Poe is generally regarded as the OG of American literature. OG, of course, stands for “Original Goth.” When it comes to the creepy, the weird, and the macabre, Poe takes his place as the grandmaster of the whole black parade. Guillermo del Toro, serving as the series editor of the Penguin Horror line, writes: “It is in Poe that we first find the sketches of modern horror while being able to enjoy the traditional trappings of the Gothic tale. He speaks of plagues and castles and ancient curses, but he is also morbidly attracted to the aberrant intellect, the mind of the outsider.” Del Toro locates Poe as the American conduit for European strains of Gothicism and romanticism, letting loose the fears of the Old World upon the New.

But viewing the emergence of the American Gothic as a transatlantic phenomenon misses more homegrown explorations into the bizarre. A century before H.P. Lovecraft (inspired by Hawthorne’s novel The House of the Seven Gables) depicted New England as a realm of terror and dread, Nathaniel Hawthorne was on the case, mining the region’s history for insights into the mind’s darker corners. Chiefly remembered today for The Scarlet Letter, that bane of high school curricula, Hawthorne’s highest achievements are actually found in his short stories. There, he examines the supposed innocence of the early American character, finding the darkness that lies beneath.

At roughly the same time that Poe was publishing stories in magazines and periodicals, Hawthorne did the same. (The House of the Seven Gables is unmistakably Gothic, but it was published after Poe established himself as the face of the genre.) Indeed, Poe himself took notice of Hawthorne’s talents. In a review, Poe wrote that “Mr. Hawthorne’s distinctive trait is invention, creation, imagination originality—a trait which, in the literature of fiction, is positively worth all the rest.” Many of Hawthorne’s finest stories were collected in Twice-Told Tales (1837), the first book he published under his own name. (He published an earlier novel, Fanshawe, under a pseudonym, like a 21st century writer self-pubbing an e-book.) As with The Scarlet Letter, many of his stories depict the early Puritan colonies of New England, well before the United States was established as a country. You can see why. Hawthorne was the descendant of New England Puritans, including his great-great-grandfather, John, who served as a judge of the infamous Salem witch trials. Hawthorne’s familial guilt over being involved in such a grotesque undertaking colors much of his work.

Hawthorne’s tales focus on communities, and the destruction that secrets can visit upon them.

Unlike Poe, whose stories often feature lonesome individuals questing into the unknown, Hawthorne’s tales focus on communities, and the destruction that secrets can visit upon them. Emblematic of this approach is “The Minister’s Black Veil.” The story takes place in a New England village during the early 17th century. Reverend Hooper, leader of the local church, arrives at the building one Sunday morning. Hooper has never been very distinctive as a minister. He acquits his duties quietly, without drawing attention to himself. But one day, without announcement or explanation, he draws an inordinate amount of attention. He arrives at church wearing a black veil over his face. The same kind of veil a mourning widow would wear.

Why does Hooper wear the veil? He refuses to say. But the

parishioners note a change in his personality. Before, his sermons were

perfunctory, even dull. But once he wears the veil, his sermonizing

becomes a full-throated performance, one that enraptures the

congregation. But rumors continue to roil the community. Does Hooper

feel guilty about some secret sin? Is that why he wears the veil? If so,

then he should simply confess the sin, and return to his normal,

unveiled self. But Hooper refuses. He gives no explanation as to the

nature of the veil, not even to his wife. He keeps the veil on for the

rest of his life. When he dies, none dare remove it, and he is laid in

the ground with his face still veiled.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου