Ι.Κονδυλάκης*

ΚΑΚΟ ΣΥΝΑΠΑΝΤΗΜΑ*(Διήγημα)

Από το βιβλίο «"Η πρωτη αγαπη" και άλλα διηγήματα του Ι. Κονδυλακη». Εκδοσεις Πελλα

Λίγα χρόνια προ του 1821 στο Κράσι της Πεδιάδας.Ο Σιφογιάννης βγήκε από το σπίτι του κιαπό πίσω η γυναίκα του φάνηκε στην πόρτα και τούπε:

— Καλιά 'χα 'γώ να μην πας, η μέρα πούνε.

— Μα δε θα κάμω δα κιαμμιά δουλειά, ευλοημένη. Δε σου τώπα; Θα πάω να δω αν είνε καιρός για διπλοσκάφισμα.

— Ο Θεός μαζή σου, μια που δε μ' ακούς. Λες πως δε θα δουλέψης· μα μπορείς τουλόγου σου να πας στα γονικά σου και να μην κάμης κιαμμιά δουλειά, και Λαμπρή νάνε;

Ο γάιδαρος περίμενε μπροστά, στην πόρτα στρωμένος, κιο Σιφογιάννης, ενώ τον έλυνε, είπε στην γυναίκα του με λίγο νεύρωμα:

— Μα σου τώπα δα, σου τώπα, πως δε θα δουλέψω. Πόσες φορές πρέπει να σου το πω;

— Εγώ 'πρεπε να σου το πω, γιατί 'νε βαρά σκόλη, και 'ξά σου. (=και ό,τι θέλεις)

— Καλά, καλά, είπεν ο Σιφογιάννης κιαφού έκαμε το σταυρό του, ανέβηκε στο γαϊδούρι και τον φώναξε «σε!» για να ξεκινήση.

Η γυναίκα του έμεινε κάμποσα λεπτά στην πόρτα και τον έβλεπε ν' απομακρύνεται. Στο αναμεταξύ μουρμούρισε:

— Μα σαν πάει μόνο για να δη, γιάειντα τον επήρε τον κλαδεύτηρο;

Ο Σιφογιάννης ήτο εξηντάρης και πάνω. Αλλά σαν αυτό δουλευτής δεν ήτον άλλος στο χωριό. Γιαυτό, αν κ' ήτο θεοφοβούμενος, η μεγάλη φιλοπονία του τον τραβούσε καμμιά φορά και τις εορτές να μη μένη αργός. Αλλ' ως ελάφρωμα στη συνείδησή του είχε την πρόφαση ότι δεν έκανε βαρειές δουλιές τις εορτές. Διόρθωνε κανένα τράφο,(=τοίχος από ξερολιθιά) πούχε χαλάσει, λευτέρωνε δέντρα από παρακλάδια ή ξεράδια, καθάριζε το χωράφι από πέτρες ή ξεχόρτιζε και κουβαλούσε το βράδυ στο σπίτι χόρτα για τα ζώα του ή ξύλα.

Κιόταν μια φορά ο παπάς τούκαμε την παρατήρηση και τούπε πως ήτο πολύ «ταμακιάρης», δηλαδή πλεονέκτης, ενώ, ως άτεκνος που ήτο, δεν είχε πολλές ανάγκες, ο Σιφογιάννης κύταξε γύρω, για να μην ακούση κανείς κείνο που θάλεγε, κέπειτα σιγά:

— Δε θωρείς τα πλούτη μου, γέροντα; είπε. Δουλεύγω και σάλιο δεν έχω στο στόμα. Δεν έχω παιδιά, μάχω αφεντικά. Πρέπει να δουλεύγω, για νάχω να πλερόνω το χαράτσι και τάλλα δοσίματα. Και σαν έχω να χορταίνω τον Αγά και το Σούμπαση( =επιστάτης του αγά ή αντιπρόσωπος ) και κάθα γιανίτσαρο που μου ζητά, γλυτόνω σκιάς απού τσι ξυλιές και χερότερα. Δουλεύγω, σα σκλάβος, για τη σκλαβιά μου.

Ο παπάς αναστέναξε:

— Και ποιος χριστιανός δεν είνε σκλάβος και δε δουλεύγει για τη σκλαβιά του;

Στο κεφάλι του ο Σιφογιάννης φορούσε μαύρη πέτσα(= κεφαλοδεσμό). Οι Ρωμιοί τότε απόφευγαν τα ζωηρά χρώματα και φρόντιζαν να φαίνωνται ταπεινοί, για να μη θεωρούνται επιδεικτικοί, ότε μπορούσαν να θεωρηθούν από τους Τούρκους προκλητικοί. Με το βάδισμα του γαϊδουριού, σειότανε η άκρη της πέτσας του Σιφογιάννη. Ήτον καθισμένος στο σαμάρι δίπλα, με ρωμαίικη καβάλα, όπως την έλεγαν τότε και την λέγουν ακόμη. Οι Ρωμιοί καβαλούσαν έτσι, για να είνε έτοιμοι να πεζέψουν, άμα φαινότανε Τούρκος. Χωρίς αυτή την έγκαιρη δουλική ταπείνωση, το μικρότερο πούχαν να υποφέρουν ήτο το ξύλο.

Σαυτή την ανάγκη βρέθηκε ο Σιφογιάννης, μόλις απομακρύνθηκε λίγο από το χωριό. Και το συναπάντημα, που τούρθε, ήτον από τα πειο επίφοβα που μπορούσαν να του τύχουν. Αντίθετα ερχόταν ένας Τούρκος έφιππος.

Από μακριά τον γνώρισε. Και ποιος δεν τον γνώριζε; Ήτον ο Αγάς του Μοχού, που λεγότανε Μόχογλους.

Την ίδια στιγμή ο Σιφογιάννης κατέβηκε από το γαϊδούρι, έσυρε το ζώο στην άκρη του δρόμου, το κράτησε 'κεί ακίνητο και στάθηκε κιο ίδιος δίπλα να περιμένη τη διάβα του Αγά. Μετά πέντε λεπτά ο Μόχογλους έφτανε μένα ψαρό άλογο. Θάτονε σαράντα πέντε ετών, αλλά φαινότανε γεροντώτερος. Ήτονε παχύς, αλλ' η κιτρινάδα τον προσώπου του μαρτυρούσε πως το πάχος τον ήτον αρρωστιάρικο. Στο βλέμμα του το άτονο και θολό φαινότανε κούραση, αλλ' η κούραση του βέβαια δεν ήτον από εργασία. Είχεν όμως στιγμές που σαυτά τα ψόφια μάτια άναβε φοβερή φλόγα ο θυμός κη τυραννική παραφροσύνη.

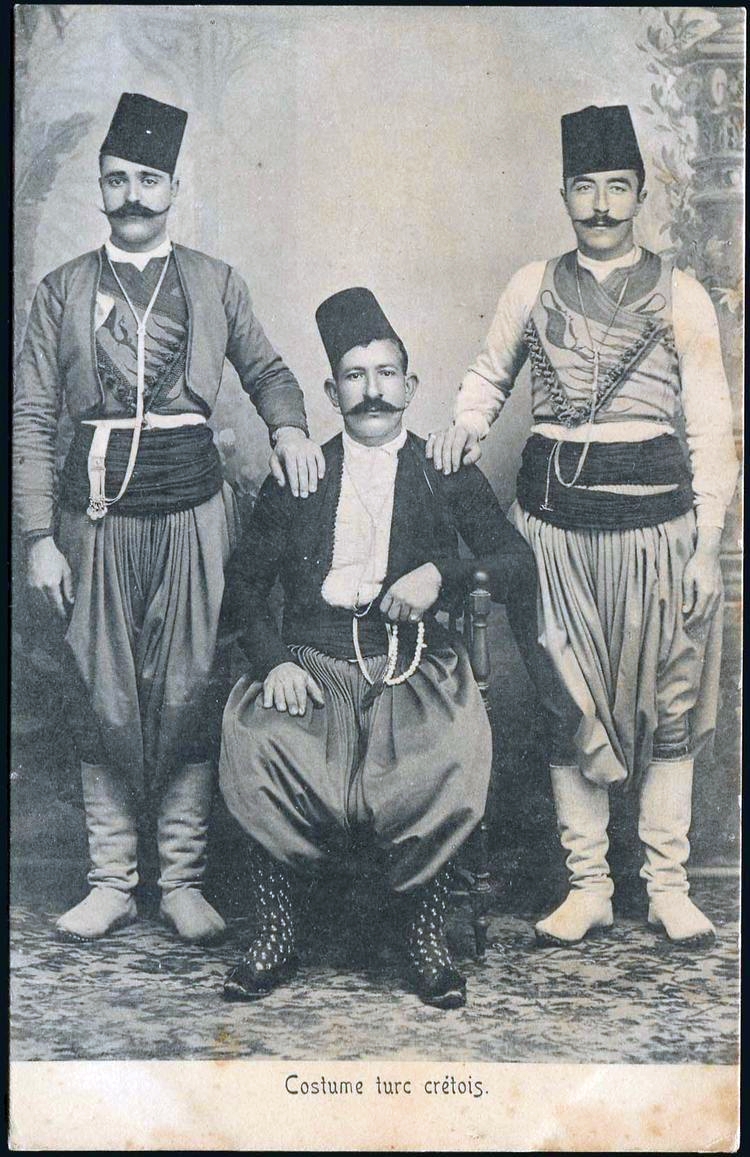

Τα σαλβάρια του ήσαν από γαλάζια τσόχα, στο κεφάλι φορούσε σαρίκι άσπρο και στη μέση του είχε μπιστόλες και γιαταγάνι.

Ο Μόχογλους ήτο, ως είπαμεν, ο Αγάς, δηλαδή ο τιμαριούχος του Μοχού και της περιοχής του. Κιως Αγάς ήτον απόλυτος κύριος της ζωής και των περιουσιών των ραγιάδων, μάλιστα τα χρόνια κείνα της γιανιτσαρικής αναρχίας, που και κατώτεροι Τούρκοι έδερναν και σκότωναν Ρωμιούς, χωρίς να δίδουν ή να χρωστούν λογαριασμόν σε κανένα.

Ο Μόχογλους δεν ήτο από τους χειρότερους Τούρκους. Είχε κάμει φοβερά πράμματα, αλλ' είχε και καλές στιγμές. Είχε σκοτώσει Ρωμιούς, για ψύλλου πήδημα ή για τίποτε εντελώς, αλλ' είχε σκοτώσει και καπανταΐδες(=νταήδες) Τούρκους που πείραξαν Ρωμιούς στην περιοχή του, τους ραγιάδες του, ως τους έλεγε. Αλλά την προστασία του άπλωνε κέξω από την περιοχή του, σε Ρωμιούς πούχε πάρει στο χαρέμι των αδερφές των ή κόρες των. Ενδεχόμενον όμως ήτο να σκοτώση μετά κάμποσον καιρόν και κείνον που έσωσε.

Είχε μια νέα υπηρέτρια χριστιανή και μια μέρα της λέει:

— Θες, μωρή, να σε παντρέψω;

— Θέλω, αγά.

— Διάλεξε τον καλλίτερο Ρωμιό ντεληκανή (=λεβέντης) να σου τόνε βλοήσω.

Η υπηρέτρια εδιάλεξε τον καλλίτερο νέο από τ' Αβδού, πούτον χωριό της· κιο Αγάς τον έστειλε παραγγελία να πάρη την υπηρέτρια του· τον έστειλε μαζή κένα φυσέκι, που σήμαινε «αν αρνηθής, θα σκοτωθής». Ο νέος, εννοείται, δέχτηκε κιο γάμος έγινε. Κουμπάρος ο Μόχογλους με αντιπρόσωπο. Μετά μια δυο μέρες πήγε η νύφη να χαιρετήση τον Αγά. Κιο Μόχογλους της είπε:

— Αρέσει σου, μωρή, ο γαμπρός;

— Αρέσει μου, αγά.

Μια πιστολιά τον Αγά την ξάπλωσε κάτω σκοτωμένη.

Αυτή όμως η ψυχική ανωμαλία του Μόχογλου δεν προερχότανε μόνον από τυραννική παραφροσύνη, αλλά, φαίνεται, κιαπό το πιοτό. Οι Μπουρμάδες, δηλαδή οι Κρητικοί πούχαν γίνει κιόλο γινόντανε Τούρκοι, είχαν συμβιβάσει στην Κρήτη το μωαμεθανισμό με το κρασί κήσαν πολλοί που κρυφά ή φανερά παράβαιναν την απαγόρευση του Μουχαμέτη. Ο Μόχογλους έπινε κρυφά, αλλά δεν έπινε για τούτο και το λιγώτερο.

Στα πέντε λεπτά, που περίμενε ο Σιφογιάννης, συλλογιζότανε σε τι διάθεση θαύρισκε άρα γε τον Αγά. Κιαν ήτο στα δαιμόνιά του, τι κακό να τον περίμενε. Θυμότανε τα λόγια της γυναίκας του και μετανοούσε που δεν την άκουσε. Ίσως η αμαρτία να δουλέψη μέρα εξαιρέσιμη (γιατ' η αλήθεια είνε ότι κάποια δουλειά πήγαινε να κάμη), τούφερε στο δρόμο του το Μόχογλου να τον τιμωρήση.

Ο Μοχόγλους όταν έφτασε, αντί να περάση, σταμάτησε το άλογό του μπροστά στο Σιφογιάννη και τούπε:

— Πού πας, μωρέ;

— Στσ' ορισμούς σου αγά. Πάω σταμπέλι μου να κάμω μια ολιά δουλειά.

— Και σήμερο δεν έχετε σκόλη, εσείς οι Ρωμιοί;

Ο Σιφογιάννης άρχισε να τρέμη.

— Ναίσκε, αγά.

— Οϊλέσα,(=δηλαδή) μωρέ, είνε κρίμα να δουλεύγη τέτοια μέρα ένας Ρωμιός;

— Ναίσκε, αγά, αποκρίθηκε ο Σιφογιάννης κέτρεμε περισσότερο.

— Το ζιμιός(=λοιπόν, άρα ) εσύ δεν είσαι καλός χριστιανός.

— Δεν είμαι, πρέπει, αγά.

— Σα δεν είσαι καλός Ρωμιός, θα σε κάμω Τούρκο.

Ο Σιφογιάννης έκαμε να παρακαλέση, αλλ' από την τρομάρα του τραύλιζε:

— Για το Θεό, αγά…και να χαρής τα παιδιά σου…

Ο Μόχογλους άγγιξε τη μπιστόλα και τούπε:

— Δε θες; Καλλίτερος είσαι συ, γκιαούρη, από 'μένα πούμαι Τούρκος;

— Όι, αγά.

— Αι, να πης και γλίγωρα τση μπιστόλας, γιατί ανημένει.

Και την ίδια στιγμή τράβηξε τη μπιστόλα.

— Ό,τι θες, αγά. Ό,τι ορίζεις. Δικός σου είμαι.

Χωρίς να βάλη στη μέση τον τη μπιστόλα, ο Μόχογλους τούπε:

— Έβγα σαυτονέ τον τράφο, μωρέ!

Ο Μόχογλους είχε στο στόμα ένα σαρδώνιο γέλιο· μαπό το σαστισμό του ο Σιφογιάννης κιαπό το δουλικό φόβο που δεν τον άφηνε να σηκώση το βλέμμα στο πρόσωπο του Αγά, δεν είδε τίποτε. Ανέβη ως τόσο στον ξερότοιχο με αρκετή δυσκολία από την τρομάρα που τον κρατούσε σ' όλα του τα μέλη. Τουρτούριζε ο κακομοίρης και τα δόντια του κτυπούσαν. Τότε ο Μόχογλους του είπε:

— Ό,τι σου λέω να λες!

Είτε από το σαστισμό του, είτε διά να γίνη ευάρεστος στον Τούρκο, είπε στην απόκρισή τον μια τούρκικη λέξη από τις ολίγες πούξερε:

— Πεκ έυ, αγά, (Πολύ καλά).

Ο Μόχογλους άρχισε ν' απαγγέλη με τόνον ιερατικής ευχής:

Τούρτουρος και τουρτουρίνα!

Ο Σιφογιάννης επανάλαβε:

Τούρτουρος και τουρτουρίνα!

Κιο Μόχογλους εσυμπλήρωσε:

Και μεγάλη Τουρκαρίνα!

Αφού επανάλαβε και τη δεύτερη φράση ο χωρικός, ο Αγάς του είπε:

— Αγνάντισες(=βλέπεις) εδά, μωρέ, είντα γίνηκε;

Με δειλό νεύμα φανέρωσε ο Σιφογιάννης πως δεν κατάλαβε.

— Θα σου το πω, εγώ, είπεν ο Μόχογλους. Ετούρκεψά σε. Και να μου γνωρίζης και χάρη που σε περιτομήγλύτωσα από το σουνέτι.(=περιτομή) Από σήμερο και πέρα είσαι Τούρκος. Θα παίρνης αμπτέστι(=καθαρμός) και θα προσκυνάς, σαν Τούρκος.

Ο Σιφογιάννης έκλινε την κεφαλήν.

— Στσ' ορισμούς σου, αγά…μα…

— Μα και μα δεν έχει! Είσαι Τούρκος. Σου δίδω κιόνομα τούρκικο· Τζαφέρης.

Έκλινε πάλιν την κεφαλήν τον ο χωρικός, χωρίς να πη λέξη.

— Άιντε δα, είπεν ο Μόχογλους, και να μην ακούσω πως πίνεις κρασί. Κατές πως ο προφήτης μας είπε να μην πίνωμε κρασί. Εγώ που θωρείς δεν το βάνω ποτέ στο στόμα μου. Είνε μεγάλο κρίμα. Ντοαλέρ(=στο καλό), Τζαφέρ αγά!

Ο Μόχογλους, αφού έβαλε την μπιστόλα στη μέση του, εφτέρνισε τάλογό τον κέφυγε· κιο Σιφογιάννης έμεινε στο δρόμο μόνος με την απελπισία του. Το χοντρό και μαύρο του χέρι σπόγγισε ίδρωτα αγωνίας από το μέτωπό του.

— Α! γυναίκα, γυναίκα, είπε μαναστεναγμό, καλά που μούλεγες και δε σάκουσα. Να η αμαρτία που μέφερε, Κεδά είντα θα κάμω;

Μια στιγμή κίνησε για να γυρίση στο χωριό· αλλ' ευθύς άλλαξε γνώμη και τράβηξε κάτω προς ταμπέλι, όπου πήγαινε. Στο κεφάλι του ήτο ένα φοβερό κιαξέμπλεχτο ανακάτωμα. Μια φορά που ο Μόχογλους τούπε να γίνη Τούρκος, πώς μπορούσε να παρακούση; Η τιμωρία του θα ήτο θάνατος, αφού και χωρίς αιτία σκότωνε. Αλλά και να χάση την πίστη του έτσι; Ο πατέρας του κοι πρόγονοί τον με τόσα που υπόφεραν εφύλαξαν τη θρησκεία των· κιαυτός για μια φοβέρα θαλλαξοπίστιζε; Πάλι όμως δεν εύρισκε μέσα του αυταπάρνηση μαρτυρική· κι άμα έφτανε στη σκέψη να παρακούση τον τύραννο κιας πέθαινε για τη πίστη του, ξέφευγε και ζητούσε τρόπο να σώση και την πίστη και τη ζωή του. Να πάη στον Αγά και να πέση στα πόδια του; Ούτε θα τον άφηναν να μπη στο κονάκι του. Αλλά και πάλι η μπιστόλα θα του μιλούσε. Να βάλη άλλον να μεσιτέψη; Ποιόν; Αλλά κιαφού μπροστά στο Μόχογλου δέχτηκε ο ίδιος να γίνη Τούρκος, μαρτύρησε πίστη στο Μουχαμέτη. Και τώρα αν έμενε χριστιανός, ήτο ως να γύριζε από την τουρκική στη χριστιανική θρησκεία. Κιαυτό θα ήτο η εσχάτη προσβολή κατά των Τούρκων και της θρησκείας των. Μια μόνη διέξοδο έβλεπε· να είνε στο φανερό τούρκος και στο κρυφό χριστιανός.

Οι περισσότεροι στην Κρήτη πούχαν τουρκέψει και τούρκευαν, αυτή την απόφαση έπαιρναν. Γιαυτό κιαλλαξοπίστιζαν όλοι μαζή οι κάτοικοι των χωριών. Αλλ' είτε κοι ίδιοι, είτε οι απόγονοί των, σε μια ή δυο γενεές, συνείθιζαν να ζουν ως Τούρκοι και τότε αληθινά απαρνούντο την καταδιωγμένη θρησκεία των. Ήτο όμως και πολύ δύσκολο, πολλάκις κιαδύνατο να κρατήσουν την απόφασή των, να κάνουν κρυφά τους τύπους της χριστιανικής λατρείας και φανερά να περνούν ως Τούρκοι.

Ο Σιφογιάννης πέρασε όλο ταπόγεμα σταμπέλι του· κιόλη την ώρα καταγινότανε σε διάφορες μικροδουλιές, αλλά πραγματικώς δούλευε το μυαλό του και βασανιζότανε νάβγη από το φοβερό αδιέξοδο, που τον είχε βάλει ο Μόχογλους. Και τρόπο να γλυτώση δεν εύρισκε.

Μόνο μια ελπίδα είχε· ότι ο Αγάς ήτο μεθυσμένος, ότι το μεθύσι του τον έβγαλε σαυτό που τούκαμε κιότι την άλλη μέρα θα το λησμονούσε. Πώς μπορούσε νάνε σοβαρό ένα τέτοιο τούρκεμα; Είχε ακούσει πως κιάλλους χριστιανούς είχαν προ ετών τουρκέψει μόνο με λίγα λόγια ενός ιμάμη,(112) αλλά σαυτή την περίσταση ήτο τουλάχιστον ένας αντιπρόσωπος της μωαμεθανικής θρησκείας. Πώς να θεωρηθή λοιπόν αληθινό το τούρκεμα πούγινε στο δρόμο κιαπό τούρκο που δεν είχε κανένα ιερατικό αξίωμα; Αλλ' αν το πράμμα δεν είχε τυπικό κύρος, είχε όμως πραγματικό. Αφού τώθελε ο Μόχογλους κη μπιστόλα του να γίνη τούρκος, ήτον αναγκασμένος να γίνη. Και δεν ήτο το ίδιο; Δεν θα πήγαινε πεια στην εκκλησία, αλλά στο τζαμί, δεν θα λεγότανε Γιάννης, αλλά Τζαφέρης. Και πάντα θα κολαζότανε. Μπορούσε να παραβή την προσταγή τον τυράννου και χωρατά αν του τώκαμε;

Ενώ έτσι σκεπτότανε, αναστέναζε κέλεγε:

— Άχι! Θε μου, δε λυπάσαι μπλειο τσοι χριστιανούς; Εξέχασές μας τσοι κακομοίριδες; Κιάρχισε κέκλαιγε.

Σε λίγες ώρες απογέρασε από τη ψυχική του αγωνία. Και τόσο αποχυμένο και χλωμό ήτο το πρόσωπό του όταν το βράδυ γύρισε στο σπίτι, που η γυναίκα του νόμισε πως ήταν άρρωστος.

— Όι, δεν είμ' αρρωστάρης, της είπε· μόνο εκουράστηκα.

Σκεπτότανε να μην πη στη γυναίκα του τη συνάντησή του με το Μόχοχλου και τα όσα ακολούθησαν, έως ότου θάβλεπε τρόπο να ξεμπλέξη.

— Εκουράστηκες; είπεν η Σιφογιάννενα. Θωρείς τα δα; Καλά το φοβούμουνε 'γώ. Μα, καλορρίζικε άθρωπε, δε φοβάσαι την αμαρτία, τέτοια σκόλη πούνε;

— Αι, ό,τι γίνηκε, γίνηκε, είπεν ο Σιφογιάννης κέπεσε σένα πεζούλι του σπιτιού. Άλλη φορά δε θα το κάμω. Μα ο Θεός το κατέει πως α δε δουλεύγω και καματερές και σκόλες, δε θα προφτάνω να μπουκόνω τσαγάδες, να μαφήνουνε να ζω.

Η Σιφογιάννενα είχε ανάψει φωτιά κ' ετοιμαζότάνε να μαγειρέψη. Δίπλα της στην πυροστιά ήτο ένα κιούπι, σκεπασμένο και δεμένο με πανί.

— Κ' είντα χαζιρεύγεσαι(=ετοιμάζεις) να μαγερέψης; ρώτησε ο Σιφογιάννης.

— Σύγλυνα (=χοιρινά κρέατα διατηρημένα στο λίπος). Αυτά που μούπεψε τσι προημερνές η συντέκνισα απού το Λασίθι.

— Σύγλυνα; ξεφώνησε με τρομάρα ο Σιφογιάννης.

— Γιάειντα; Φοβάσαι να μη μας έρθη κιανείς Τούρκος μουσαφίρης; Θε μου, βλέπε μας!

— Εγώ χοιρινό δεν μπορώ μπλειο να τρώω.

— Γιάειντα;

— Γιατί 'μαι Τούρκος.

Η γυναίκα τον παρατήρησε με απορία. Τρελλάθηκε ή χωράτευε;

— Τούρκος; Είντα λόγια 'ν' αυτά, νοικοκύρη μου;

Αποφάσισε και της διηγήθηκε πως στο δρόμο τον τούρκεψε ο Μόχογλους.

Η Σιφογιάννενα έμεινε.

— Κεδά; είπε με μισή φωνή.

— Είντα μπορούμε να κάμωμε; Τούρκο με θέλει τούρκος θα γενώ.

— Νουσουμπέτι(=αποπληξία) να τουρθή! καταράστηκε η Σιφογιάννενα, αλλά και φρόντισε να χαμηλώση τη φωνή της.

— Α δεν κάμω το θέλημά του, κατές (=ξέρεις) είντα θα γενή.

Με βαθύ αναστεναγμό η γυναίκα είπε:

— Ω Χριστέ μου!

Έπειτα:

— Κείντα θα κάμης εδά;

— Πρώτα πρώτα θα πάψω να λέωμαι Γιάννης και θα λέωμαι Τζαφέρης. Θα φορώ σαρίκι και θα πω στο χωριό πως από σήμερο και πέρα είμαι τούρκος.

Μείνανε συλλογισμένοι κάμποσα λεπτά. Έπειτα η γυναίκα είπε:

— Δεν πας να το πης και του παπά;

— Κείντα μπορεί να μου κάμη κιο κακορρίζικος ο παπάς; Να βρη το μπελλά του κιαυτός;

— Μια βουλή θα σου δώση.

Ο Σιφογιάννης πήγε την ίδια βραδιά και ζήτησε γνώμη του παπά. Αλλ' ο παπάς, ένας καλός και με θάρρος χριστιανός, του υποσχέθηκε κάτι περισσότερο· τη μεσολάβησή του:

— Θα πάω 'γώ να τόνε δω· κιο Θεός να δώση να τόνε βρω στσι καλές του. Μάνεν τόνε βρω στα δαιμόνια του, και για σένα δε θα κάμω πράμμα κεμένα μπορεί να μου δώση κιαμιά μπιστολιά. Η γιαλήθεια είνε πως όντεν έρχεται στο χωριό δε μου αγριγιομιλεί. Να σου πω κιόλας πολλά κακός δεν είνε…(είπε σταυτί τον Σιφογιάννη) μάνε κουζουλός… θαρρώ πως πίνει κιόλας.

Όσο να περιμένη την απάντηση του παπά, ο Σιφογιάννης δε βγήκε από το σπίτι του. Αν έβγαινε, έπρεπε να βγάλη τη μαύρη πέτσα και ναρχίση να κάνη εξωτερικώς τον Τούρκο. Αφήκε μια μέρα και τη δεύτερη πήγε ο πάπας στο Μοχό νάβρη τον Αγά. Κιόταν το βράδυ γύρισε, είπε στη Σιφογιάννενα από την πόρτα:

— Ανεζινιό, είν' ακόμ' από κεινά τα Λασιθιώτικα σύγλυνα; Να τα τηγανήσης μαυγά να τα φάμε μαζή.

Κιαφού μπήκε κέσπρωξε την πόρτα, είπε:

— Φέρε και κρασί. Ο αγάς μου παράγγειλε να πιούμε και στην υγειά

του.

— Καλό μουζντέ(=είδηση, νέο) μάςε φέρνεις, ευλοημένε; είπε η γυναίκα. Δόξα

σοι ο Θεός!

— Δοξασμένο νάνε τόνομά του! είπε κιο Σιφογιάννης κέκαμε το σταυρό

του.

— Ο Θεός αλήθεια έκαμε και τον εβρήκα στα καλά του, είπεν ο παπάς. Και κατές είντα μούπε; Σε 'δε, λέει, πως δεν είσαι καλός χριστιανός, γιατί πήαινες να δουλέψης μέρα σκόλη, και γιαυτό 'βαλε στο νου του να σε κάμη Τούρκο.

— Η αμαρτία, μουρμούρισε η Σιφογιάννενα.

— Δε σας είπα πως ο Μόχογλους δεν είνε κακός; Μαγάρι νάσαν κιάλλοι Τούρκοι σαν κιαυτόν. Μόνο να μην είνε στα μεράκια και τα μπουριά (=μπουρίνια, νεύρα) του. Ώστε να με δη, ένιωσε γιατί πήα κιάρχιξε να γελά. Στο ύστερο μου λέει: «Σαν τόνε θες, εσύ παπά, χριστιανό, χάρισμά σου. Ας μείνη στην πίστη σας. Και καλά 'καμες κήρθες γλίγωρα, γιατί, α μαθητευότανε πως ετούρκεψε, δε θα μπόριε μπλειο να ξετουρκέψη.

Τόσο βάρος έφυγε από το στήθος του Σιφογιάννη και τόση χάρη γνώριζε για το γλυτωμό του, που ευχήθηκε για τον τύρανο:

— Ο Θεός να του δώση τσοι χρόνους που μούκοψε!

*Ιωάννης Κονδυλάκης (1821-1920) - Βικιπαίδεια

*Ιωάννης Κονδυλάκης (1821-1920) - Βικιπαίδεια

**

************************************

AN UNFORTUNATE ENCOUNTER

By Ioannis Kondylakis*Freely adapted by Vassilis C. Militsis

A few years before 1821 at Krasi of Pedias (in Crete) Sifoyannis issued from his house followed by his wife who stood at the door addressing him:

“You’d better not go on such a holy day, I’m afraid”

“But I’m not going to do any work, bless you! Haven’t I already told you? I’ll just go and see if it’s high time for double hoeing.”

“May God be with you, since you won’t listen to me. You say you won’t work; but how is your lordship going to your lands without doing some chore or other, even on Easter day, as it is?”

The ass was tethered in front of the gate and while untying him, Sifoyannis addressed his wife vexed:

“Haven’t I just told you I shan’t be working? How many times shall I repeat it?”

“Anyway, I ought to warn you as today is a Sabbath Day – no work is allowed,” said his wife.

“All right, don’t worry,” Sifoyannis, making the sign of the cross, soothed her, rode his donkey and cried ‘giddy up’ for it to move on.

His wife stood still for a few minutes at the door seeing him ride away and murmured to herself:

“If he went only to see, why has he taken the billhook with him?”

Sifoyannis was already into his sixties. However, none in the village was such a hard worker as he. Therefore, though he was a God fearing man, his industry sometimes compelled him not to be idle even on religious days. But to relieve his conscience he rationalized that he did not do heavy work; he mended some drywall that had been eroded, freed the trees from dry offshoots and grass, cleared the field from rocks or weeded it. In the evening he carried home firewood or hay for his animals.

When once the village priest remarked that he was rather venal, since he was childless and hence his necessities were few, Sifoyannis looked around lest he could be eavesdropped and told him sotto voce:

“Look at my riches, your reverence. I break my back working but my mouth is dry of spittle. I may not have children, but I have masters. I have to work to pay the poll tax and other levies. And as long as I work enough to feed the agha and the governor as well as every janissary that demands from me, I can get away with corporal punishment. I work like a slave for the sake of my slavery.”

The priest heaved a sigh:

“And aren’t all Christians slaves working for their slavery?” he remarked.

Sifoyannis wore his petsa – his black netted headgear with fringes, wrapped around the head. The Greeks of those times shunned flashy finery so as to appear humble, and not provoke the Turks. As the donkey was trudging along, the fringes on Sifoyannis’ head were dangling to and fro. He rode sideways – the Greek way, as this manner of riding is still now called. The Greeks rode that way so that they could be ready to ride off when a Turk was at large. Without that timely humiliation the least they could suffer was a thrashing.

No sooner had Sifoyannis drawn away from the village than he found himself in that situation. And his encounter was of the most dangerous that could befall him. From the opposite direction a Turkish rider was coming. Sifoyannis recognized him even from a distance. And who could not know him? The Turk was the agha of Moho, the so called Mohoglu.

Immediately Sifoyannis dismounted and drew his beast to the edge of the road, held it still and stepped back to let the agha pass by. After five minutes Mohoglu mounted on a gray steed arrived. He must have been forty-five years old though he looked older. He was corpulent but the paleness of his face betrayed a sickly disposition. His languid and dim eyes also showed weariness, which was not due to work. However, there were moments when those limpid eyes were aflame with terrible anger and tyrannical madness. He wore wide trousers made of blue baize and his head was covered with a white turban; his pistols and saber were stashed in his sash around his waist.

Mohoglu was the agha, the feudal lord of Moho and its region, and as an overlord he had full sway on the lives and properties of the reaya. Indeed, during those years of janissary anarchy even Turks of the lower classes used to beat up or even kill Greeks without being answerable to anyone.

Mohoglu, however, did not belong to the worst kind. He had done terrible things, but he also had his kind moments. It was true that he had killed innocent Greeks for the drop of a hat, but he had also killed Turkish bandits that harassed his reaya Greeks of his region, as he liked to call them. His protection was also extended outside his region, to the Greeks whose sisters or daughters he had taken in his harem. It was also possible after some time for him to kill someone who had spared before.

Once he asked a Christian girl who was in his service:

“Hey you, do you want me to marry you off?”

“I do, my lord.”

“Then pick out the best Christian stalwart youth, and I will bless you both.”

The servant girl chose the best youth in Abdou, her home village. The agha sent for him to marry the girl. He accompanied his order with a bullet, which meant: “if you refuse, you’ll lose your life.” The youth naturally accepted to marry the girl; they were married at the village and the best man was Mohoglu by proxy. After a couple of days the married couple paid the agha a courteous visit.

“Hey girl,” asked Mohoglu, “do you like the bridegroom?”

“I do, my lord,” she replied.

Whereupon the agha drew his pistol and with a shot sent her flat, dead upon the floor.

Mohoglu’s mental aberration did not only originate in his tyrannical paranoia but also in his heavy drinking. The Cretan renegades, who were continually converting to Islam, had compromised wine with their new faith and many of them secretly or in the open violated Muhammad’s injunction against alcohol. Mohoglu drank under the counter, but not necessarily a little.

While Sifoyannis waited for the few minutes for the agha to pass by, he mused on what mood he would find him. And if the agha was in a bad temper, what misfortune would befall him? He recalled his wife’s words and repented that he had not listened to her. Perhaps it was sinful to work on such a religious day (for he was going to do some work). That was why fate had brought Mohoglu as a punishment.

Instead of ignoring him and passing by, Mohoglu reined in his horse in front of Sifoyannis and asked:

“Hey, where are you off to?”

“At your service, agha. I’m going to my vineyard to do some work.”

“But today don’t you Greeks keep the Easter rest?”

“Indeed, my lord,” replied Sifoyannis and began to shake all over.”

“So, isn’t it a sin for a Greek to work on such a day?” Agha asked again.

“Indeed, my lord,” Sifoyannis responded and his trembling grew more violent.

“Therefore, you aren’t a good Christian,” ruled the agha.

“I must not be, my agha.” Said Sifoyannis.

“Since you aren’t a good Greek and a Christian, I’ll turn you into a Turk,” said the agha.

Sifoyannis attempted to beg, but his terror made him stutter.

“For the love of God, my agha… may your children be happy…”

Mohoglu felt his pistol.

“Do you refuse? Do you believe, infidel, you’re better than me that I’m a Turk?”

“Nay, my lord.”

“Say aye and fast or the pistol is ready,” and saying this he drew the weapon.

“As you wish, my agha. At your command; I’m all yours.”

Without putting the pistol back in his sash, Muhoglu told him.

“Get on that drywall.” A sardonic grin played on Mohoglu’s mouth. Because of his daze and his obsequious fear, Sifoyannis could not lift his eyes to the agha’s face. Thus he had not seen the low drywall. He stepped on it with some difficulty because of the trembling that possessed all his limbs. The poor man was shuddering and his teeth were gnashing. Then Mohoglu told him:

“Repeat after me!”

Whether out of fear or in his attempt at ingratiating himself with the Turk he responded with a word of the few he knew in Turkish. “Pek iyi (very well), agha.”

Mohoglu then began to recite in tones of religious incantation:

“Turturos and Turturina!”

Sifoyannis repeated:

“Turturos and Turturina!”

And Mohoglu added:

“And great Turkarina!”

After the peasant repeated the latter phrase, the agha asked him:

“Do you understand what’s just happened?”

Sifoyannis shook his head timidly that he doesn’t.

“I’ll tell you,” said Mohoglu. “I’ve turned you into a Turk; and be grateful to me that I’ve let you get away with sünnet (circumcision.) You shall keep abdest (ritual ablution) and salat (pray bowing) like a Turk.

Sifoyannis bowed his head.

“At your command, my agha… but…”

“Don’t but me! You’re a Turk now and I’m giving you a Turkish name: from now on your name shall be Jafer.”

The peasant bowed his head again not daring to utter a single word.

“Go now,” said Mohoglu, “and let me not hear that you’ve been drinking wine. Look at me; I have never drunk a drop of it. It’s a great sin. Goodbye now, Jafer agha!”

Putting his pistol back into his sash, he spurred his horse and rode off. Sifoyannis stood in the middle of the road alone and disconsolate. He wiped the sweat off his brow with his dark, rough hand.

“Ah wife!” he sighed, “you were right but I wouldn’t heed your advice. And that’s what my sin has brought me to. What am I to do now?”

He was half-a-mind to go back to the village but he finally stuck to his original plan and headed for his vineyard.

His mind was in utter confusion. Once Mohoglu converted him into a Turk, how could he disobey him? His punishment would be death, for Mohoglu was wont to kill without any provocation. On the other hand, he ought not to denounce his faith. His father and forefathers preserved their religion much as they suffered; and should he become a renegade after a mere threat? Nevertheless he could not find within him the self-abnegation of a martyr. And when he considered disobeying the tyrant at the expense of sacrificing himself for his faith, he sought a way to save both his faith and his life. Shall he go to the agha and prostrate himself to implore him? He would not be even allowed to enter his mansion; let alone the agha’s pistol would have the upper hand. Shall he get someone to intercede? But who would that be? Didn’t he agree before Mohoglu to become a Turk and proclaim faith to the prophet? And now if he still remained Christian, it was as though he were reconverting from Islam to Christianity, which would be the capital insult against the Turks and their religion. Therefore, he saw only one choice: to be a Turk in the open and a secret Christian.

Most Cretans that had become or were becoming Turks made that decision. That was why whole villages were easily converting. But the neophytes and their following generations got used to living like Turks and eventually repudiated their persecuted religion; for it was indeed difficult, and often impossible, to stick to their choice, i.e. to secretly preserve the rites of Christian worship and pass themselves off as Turks.

Sifoyannis spent the whole afternoon at his vineyard. He kept himself busy with small jobs, but in reality he was in vain trying to think of a way to come out of that horrible dead end Mohoglu had put him in. But no way could he find to extricate himself of that entanglement.

There was only one hope left; the agha might have been drunk, and what he had done was the aftermath of his intoxication and perhaps he would forget it all the next day. How could such a conversion be serious? He heard that others had changed into Muslims in the presence of an imam, but in that case it was done by a clerical of the Islamic faith. But how could a conversion considered real while done on the street and by one possessing no religious office? At any rate, if the deed was not officially valid, notwithstanding, it was real. If Mohoglu and his pistol wanted him a Turk, he had to be a Turk. Thus, it was the same. No longer would he be going to church, but he would be worshipping at a mosque; no longer would his name be Yannis; he would answer to the name of Jafer. He would be in constant sin. Could he disobey the tyrant’s command though it had been given in jest?

Thus he brooded, sighing and saying:

“Oh God! Do you have no mercy on Christians? Have you forsaken the poor wretches?” And then he began to weep. In a few hours the turmoil of his soul abated somewhat, but on arriving back home in the evening his countenance was so haggard and pale that his wife thought he was unwell.

“No,” he assured her; “I’m not ill, only a bit tired.”

He was contemplating not to tell his wife of his encounter with Mohoglu and what had followed until he found a way out of it all.

“Tired, eh?” said his wife. “Do you see now? I was afraid of it. Aren’t you afraid of sinning, ill-fated man, on a holy day as it is?”

“Ah, what’s done is done,” said Sifoyannis and collapsed onto a stone bench. “I won’t do it again, but God knows that if I don’t work both weekdays and holidays, I’ll be short of feeding the aghas so they can let me live.”

His wife had built a fire and was about to cook a meal. Beside the trivet by the hearth there was a jar covered with a piece of cloth and tied around its neck.

“What are you going to cook?” asked Sifoyannis.

“Syglina (pork meat preserved in fat). The ones our best man’s wife sent from Lassithi the other day.” She replied.

“Syglina,” Sifoyannis exclaimed in dismay.

“Why not? Are you expecting a Turkish guest and you’re scared? Oh dear God! Have mercy upon us!”

“I may no longer eat pork”.

“Why not?”

“I’m a Turk.”

His wife looked at him in wonder. Was he mad or joking?

“A Turk? What are you talking about, my husband?”

At last he decided to tell her that Mohoglu had converted him on the way to his vineyard.

Sifoyannis’ wife was transfixed.

“What now?” she asked.

“And what can be done? He wants me a Turk; Turk shall I be.”

“A fit upon him!” his wife put the curse upon the agha, but she took the precaution to lower her voice.

“Unless I do his will, you know what’ll happen.”

“Oh, Christ!” and she went on:

“And what will you do now?”

“First I’ll stop be Yannis and will be Jafer. I’ll be wearing a turban and I’ll tell the village I’m a Turk through and through.”

They both remained silent, lost in thought. Then the woman suggested:

“Why don’t you tell the priest, too?”

“And what can the poor priest do more besides landing in trouble himself?”

“He might give you some advice.”

Sifoyannis went to the priest that evening to seek his counsel. The priest was a good and brave Christian, and beyond Sifoyannis’ expectations he promised to mediate to the agha.

“I’ll go and see him,” he said; “but if I find him in his tantrums, I may not do anything for you and besides he might even shoot me. It is true that he’s meek with me whenever he comes to the village. I don’t think he is too bad… (he whispered in Sifoyannis’ ear) but he’s insane, and besides, I think, he’s rather fond of liquor.”

While he was waiting for news from the priest, Sifoyannis did not budge from his house, because he would have to discard his petsa and make his appearance as a Turk. They let a day pass and on the following the priest went to Moho to seek the agha. Upon returning in the evening he hollered Sifoyannis’ wife at the door:

“Anezinio, have you still got the syglina from Lassithi? Fry them with a couple of eggs in the pan and let’s relish them all together.”

And pushing the door the priest stepped into the house.

“Bring some wine, too, so we may drink to the agha’s health.”

“You’ve brought us good tidings, your reverence.” Said the woman. “Thank God and may He bless you, too!”

“Glorious be His name!” said Sifoyannis crossing himself.

“In sooth, God helped me to find the agha in a good mood,” added the priest. “And guess what he told me: ‘he saw that you weren’t a good Christian, as you were going to work on such a holy day, and thought it advisable to make you a Turk.’”

“The sin!” murmured the woman.

“Haven’t I already told you,” said the priest, “that Mohoglu isn’t that bad? I wish other Turks would be like him, too. His bad point is only when he’s in a bad temper. And then he told me: ‘if you want him a Christian, priest, he’s all yours. Let him remain in your faith. And you did well to come to me soon, because if it had gone around that he turned into a Turk, he could no longer have changed back.’’’

Such a heavy burden was off Sifoyannis’ chest and so grateful he felt for his deliverance that he even prayed for the tyrant:

“May God the days the agha took off me change them into long years for him!”

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου