Ο ποιητής Σααντί Σαραζί και ο Κήπος με τα Ρόδα

Sa’di’s remarkable poetry is perpetually modern and full of ‘benevolent

wisdom’ on how to live. Joobin Bekhrad revisits the life and work of

‘the cheerer of men’s hearts’.

I

In

the 13th Century AD, during one of the most turbulent periods in

Iranian history, the poet Sa’di left his native Shiraz to study in

Baghdad. From there, he went on to travel far and wide, and it was

around three decades before he returned home to his city of roses and

nightingales, which, thanks to the diplomacy of Shiraz’s occupying

Turkic rulers, had been spared the terror that the Mongols had unleashed

elsewhere in Iran.

Despite being an acclaimed poet in the region, Sa’di

felt he’d wasted his life so far and had said nothing of consequence,

and so resolved to spend the rest of it in silence. At the insistence of

a friend, however, he broke his vow, and, it being springtime in

Shiraz, the two went for a stroll in a paradise garden. Surprised that his friend should choose to gather flowers and herbs in his robes, Sa’di remarked in Khayyam-esque

fashion on the ephemerality of such things, and promised his friend

that, instead, he would write a book both enjoyable and educational

called the Golestan (Flower Garden), whose pages would last forever.

In spite of the inhumanity and terror surrounding him, Sa’di had faith and hope in mankind

The

poet kept his word – and was right. Together with the Bustan (Garden),

his other best-known book, the Golestan remains one of the most beloved

works of Persian literature many centuries on. “Created from one

essence, people are members of a single body,” Sa’di wrote in what today

is not only his most-quoted poem, but perhaps also the most famous poem

in the Persian-speaking world. “Should one member suffer pain, the rest

shall, too. You who feel no sorrow for the distress of others cannot be

called a human being.”

If

other medieval Persian poets are revered for their ecstatic writings on

love, tales of chivalry and derring-do among the heroes of old Iran, or

insights on the human condition and man’s place in the grand scheme of

things, Sa’di is, as Lord Byron aptly called him, “the moral poet of

[Iran]”. In spite of the inhumanity and terror surrounding him, Sa’di

had faith and hope in mankind, and as such devoted much of his attention

to explaining morals and ethics while enjoining his readers to

cultivate more noble qualities within themselves. “Ask not,” he

admonished, “a dervish in poor circumstances, and in the distress of a

year of famine, how he feels, unless thou art ready to apply a salve to

his wound or to provide him with a maintenance.” Sa’di also believed

that “a liberal man who eats and bestows is better than a devotee who

fasts and hoards”.

As much as he advocated goodness, however, Sa’di was

also a very practical and realistic thinker. His circumstances – Sa’di

lived in “a very violent and brutal world,” Persian literature scholar

Dick Davis tells BBC Culture – no doubt had much to do with this fact.

“A falsehood resulting in conciliation is better than a truth producing

trouble,” Sa’di wrote in the Golestan. Similarly, he warned

“not [to give] information to a [prince] of the treachery of anyone,

unless thou art sure he will accept it; else thou wilt only be preparing

thy own destruction”. Just as the Golestan and Bustan had much to say

about the strange, uncertain times in which Sa’di lived, so too do they

have wisdom to impart concerning the current pandemic.

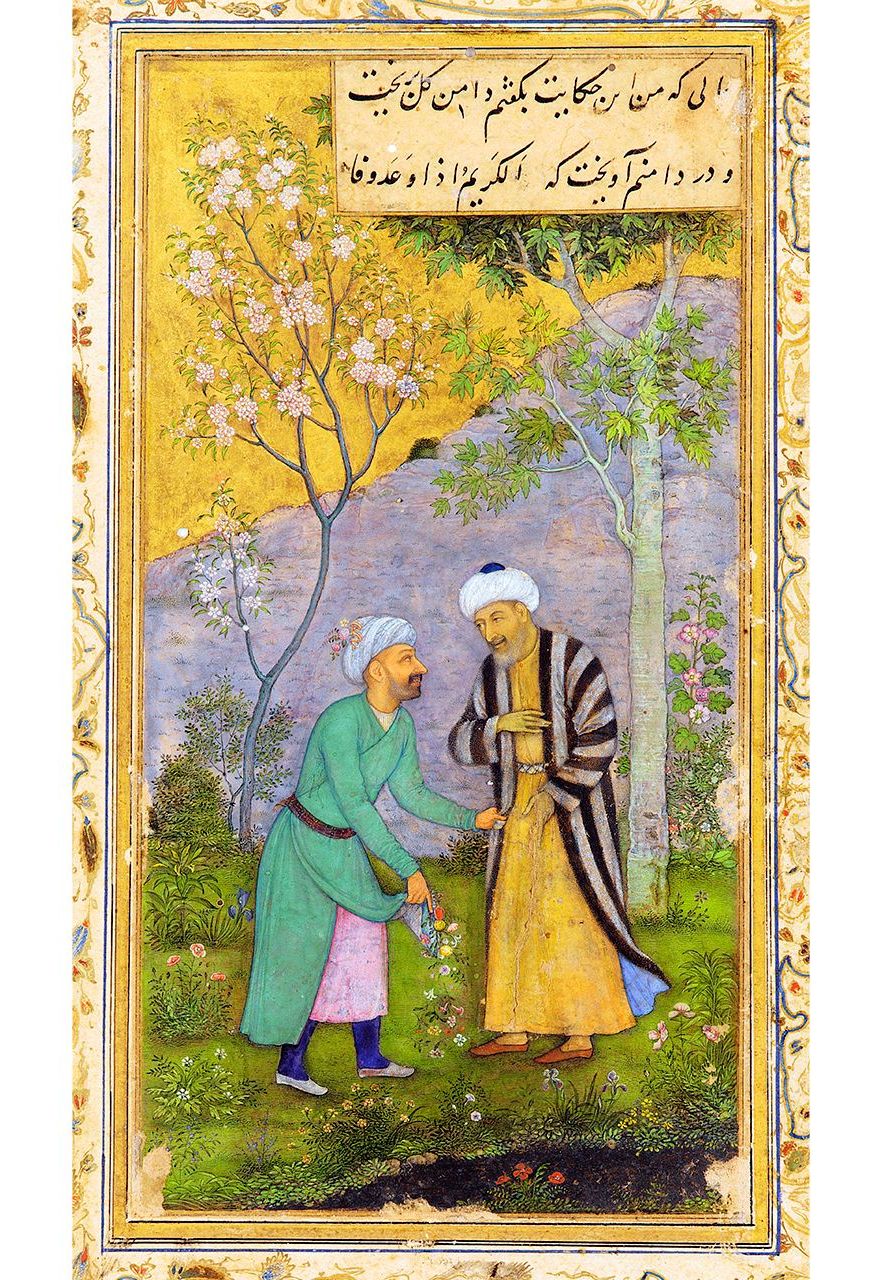

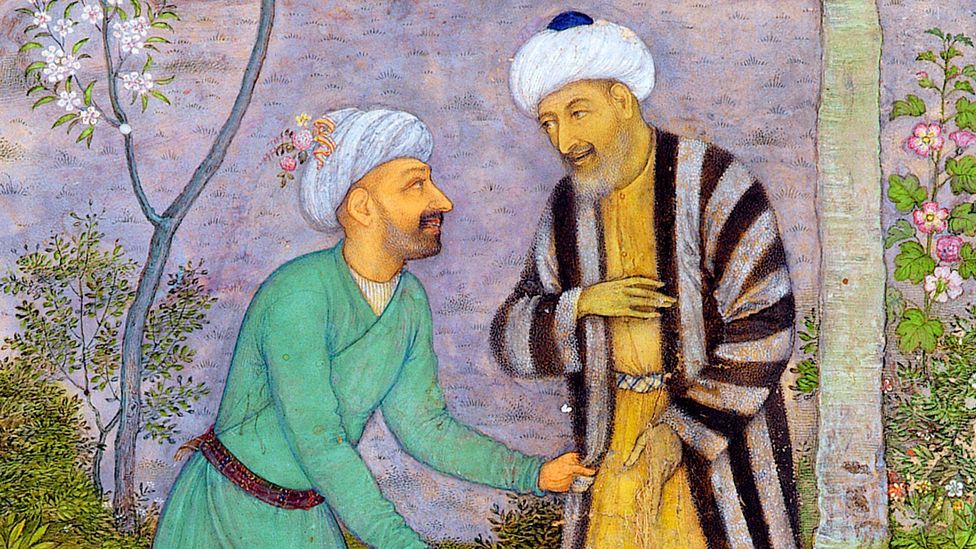

The poet had the idea of writing his book Golestan (Flower Garden) while strolling with a friend in springtime (Credit: Alamy)

Earlier

that century, the poet Rumi had fled the Mongols, while still a child,

leaving his native Balkh to travel westwards with his family. This was,

as it turned out, a wise move – another mystic Persian poet, Attar of

Neyshapur, was murdered at the hands of the Mongols soon afterwards.

Could it be that Sa’di, who left Shiraz just after the Mongol massacres

in eastern Iran, embarked on his travels for the same reason? According

to Davis, however, it is unknown why, exactly, Sa’di left his hometown.

“The short answer is we don’t know,” he says.

Much of what Sa’di says about his travels are to be taken with a grain of salt. In the Golestan and Bustan, for

instance, Sa’di claims to have been taken captive by Crusaders in

Syria, and visited Kashgar (in present-day China) as well as India. “His

implication that he was captured by Crusaders and held as a slave for a

while is now thought to be an invention,” says Davis. Likewise, Dr Homa

Katouzian believes that it is probable Sa’di visited places like Syria,

Palestine, and the Arabian Peninsula, but not Khorasan (ie the eastern

Iranic lands), Kashgar, or India. It can be said, though, that Sa’di

certainly did travel outside of Iran, and returned after a lengthy

absence with much to tell. His words are not those of a cloistered

mystic, but a man of the world.

Sa’di himself hints in the Golestan that some of his tales might not have a factual basis. But as he told his friend in the garden, he set out to not only instruct, but also entertain. As such, the Golestan and Bustan, though

chiefly guides to life, also have the qualities of travelogues and

adventure stories at times. In them, the reader encounters bands of

brigands, sailors at sea, assassins, and fearsome rulers, among other

characters. Some of his anecdotes can even be read as jokes. In the

chapter about the advantages of silence in the Golestan, for

example, Sa’di tells of a tuneless reciter of holy scripture. “A pious

man passed near, and asked [the reciter] what his monthly salary was. He

replied: ‘Nothing.’ He further inquired: ‘Then why takest thou this

trouble?’ He replied: ‘I am reading for God’s sake.’ He replied: ‘For

God’s sake, do not read’.” As David Rosenbaum notes in the introduction

to Edward Rehatsek’s 19th-Century translation of the Golestan, “[Sa’di]

makes the reader forget that he’s being taught something; the medicine

of Sa’di’s verse is honeyed”.

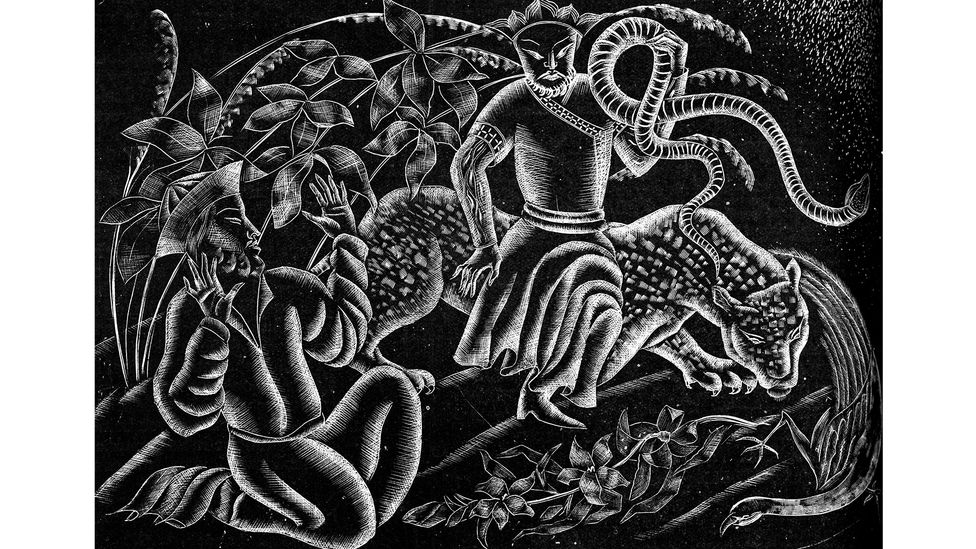

A 1920s wood engraving by Cynthia Kent was used to illustrate Sa’di’s works in translation (Credit: Alamy)

Although

Sa’di wrote in the Golestan that it was the first book he penned after

breaking his vow of silence, the Bustan actually precedes it by a year.

Alternatively known as the Sa’di Nameh (Book of Sa’di), it is a book of

poetry divided into 10 chapters. The Golestan, on the other

hand, is a book of prose punctuated at times by poetry, and consists of

eight chapters dealing with similar topics. Both were written under the

patronage of the Salghurid rulers of Shiraz (the poet’s nom de plume is

a homage to the dynasty, whose name was Sa’d), and in many cases Sa’di

discusses the proper conduct for kings and ministers; but, unlike the

11th-Century Ghabus Nameh (Book of Ghabus), they are not directed solely

at rulers-to-be. “The Golestan and Bustanare meant as mirrors for everyone,” says Davis. “They are part of a long tradition of homily/advice/how-to-live/what-to-do literature in Persian.”

In the Bustan, Sa’di expounds on subjects like

contentment, gratitude, benevolence, and humility, while the Golestan

contains stories about the morals of dervishes, the trials of old age,

and contentment, again, among other subjects and numerous general

maxims. Recurring themes can be found in both. According to Sa’di, it’s

better to suffer from want than to beg and become indebted to someone

else. He also says that we should be careful what we wish for, because

we might find ourselves worse off; that before people accuse another,

they should first take a look at themselves; that silence is golden;

that spiritual wealth is superior to material wealth; and that fate

trumps one’s will. Some of Sa’di’s views are rooted in religion, and he

isn’t always what one would today call politically correct; but for the

most part, his advice is timeless and far from being restricted to its

medieval Iranian context.

Benevolent wisdom

Amongst the first Persian poets to achieve renown in

Europe, Sa’di had a marked influence on Enlightenment and Romantic

writers in France and elsewhere, such as Voltaire, Diderot, Goethe, and

Victor Hugo, who quoted some of the Golestan’s introductory passages

regarding the garden story in the epigraph of Les Orientales. And, while

Voltaire jokingly attributed the preface to the tale of his Zoroastrian

hero Zadig to Sa’di, the poet’s presence in this major work was more

than superficial. “The model king of Serendip, his vizier, the perfect

society, are all modelled closely on Sa’di… The anticlericalism and

criticism of human egotism, too, recall the Persian poet,” writes Dr

Mozaffar Bekhrad in his book The Literary Fortunes of Sa’di in France. “In

Sa’di, Voltaire found a true guide to philosophy,”, he remarks, to the

extent that “his arch enemy, Élie Fréron, began to use ‘Sa’di’ as a

sobriquet for Voltaire in critical attacks”.

In the US, Sa’di greatly inspired Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In his eponymous poem in praise of the poet (Saadi), Emerson called

Sa’di “the cheerer of men’s hearts”, and commented on the universal

appeal of his “benevolent wisdom”: “Through his Persian dialect,” wrote

Emerson in his introduction to Francis Gladwin’s translation of the

Golestan, “he speaks to all nations, and, like Homer, Shakespeare,

Cervantes, and Montaigne, is perpetually modern”. It is perhaps for this

reason that in the United Nations headquarters in New York there is a Persian carpet,

embroidered with the famous verses from the Golestan concerning the

unity of mankind, which Barack Obama quoted in his 2009 Iranian New Year

message. “There was some awareness in that administration of Iranians’

love of poetry,” says author and political commentator Hooman Majd, “and

the notion of speaking to the Iranian people in a respectful way was

Obama’s. I imagine his speechwriters got the input from someone aware of

the carpet”.

Go and give thanks that, though thou ridest not upon a donkey, thou art not a donkey upon which men ride – Sa’di

The

Golestan and Bustan certainly influenced Voltaire and Emerson, but what

can we learn from them today? There is in fact plenty of pand (advice) that pertains to the coronavirus pandemic. In the Bustan, Sa’di

exhorts his readers to be generous to the needy – “lest thou should

wander before the doors of strangers” – as much as possible. “If thou

hast not dug a well in the desert, at least place a lamp in a shrine.”

He also reminds us that we require far less than we think. “What need

have I of a lofty roof?” a holy man asks a critic who says he can build a

better house. “This that I have built is high enough for a dwelling

which I must leave at death.”

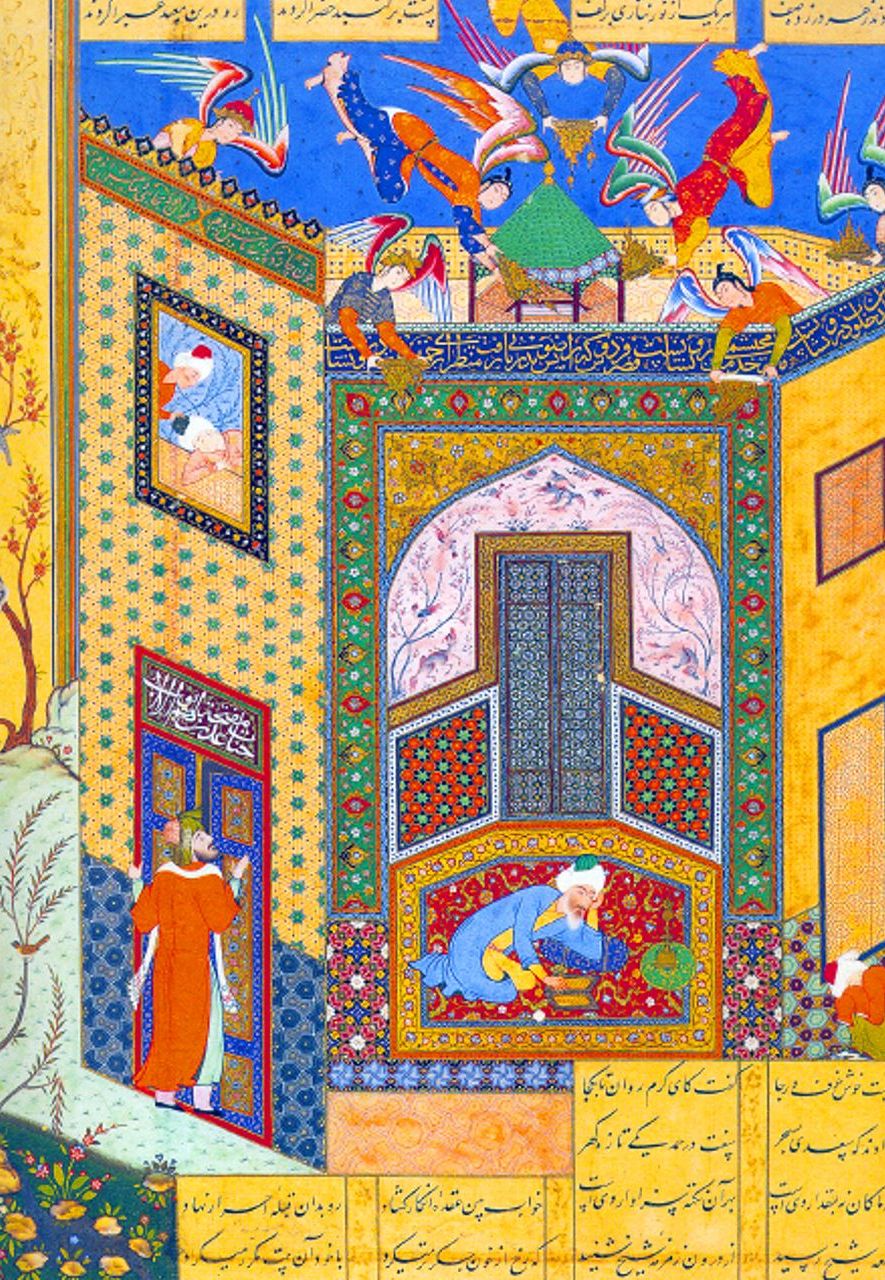

Sa’di is the central figure in this 16th-Century manuscript that highlights the poet’s mysticism (Credit: Alamy)

Similarly,

the Persian emperor Ardeshir-e Papakan is rebuked by his physician for

thinking that “living is for eating” rather than the opposite, and

elsewhere, Sa’di tells of the fate of a glutton who fell from a tree on

account of his weight. Sa’di also advises his audience to be grateful

for and cherish what they have. “He knows the value of health who has

lost his strength in fever. How can the night be long to thee reclining

in ease upon thy bed?” Or, as a donkey puts it to a straggler elsewhere,

“Go and give thanks that, though thou ridest not upon a donkey, thou

art not a donkey upon which men ride”.

There’s also a story in the Golestan that illustrates

the dangers of not using one’s common sense and blindly following the

advice of those not qualified to give it. A man suffering from an

eye-sore visited a farrier, who applied to his eyes the medication he

used on the hooves of horses. Not surprisingly, the man went blind, and

his complaint against the farrier was dismissed by the judge. “Had this

man not been an ass,” said the judge, “he would not have gone to a

farrier”. Lest there be any misunderstanding, Sa’di clarifies the moral

of the story: “Whoever entrusts an inexperienced man with an important

business and afterwards repents is by intelligent persons held to suffer

from levity of intellect.”

Many autumns have passed since Sa’di composed the Golestan and Bustan. Yet,

just as he predicted centuries ago after returning to Shiraz – where

his tomb, aptly situated in a resplendent garden, continues to attract

flocks of visitors – the pages of these Persian books of wisdom have

more than stood the test of time. In the poet’s words: “Five days or

six – a flower’s life is brief; this garden, however, is ever sweet”.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου