May 8, 2017 · 9 min read

Source: eidolon.pub

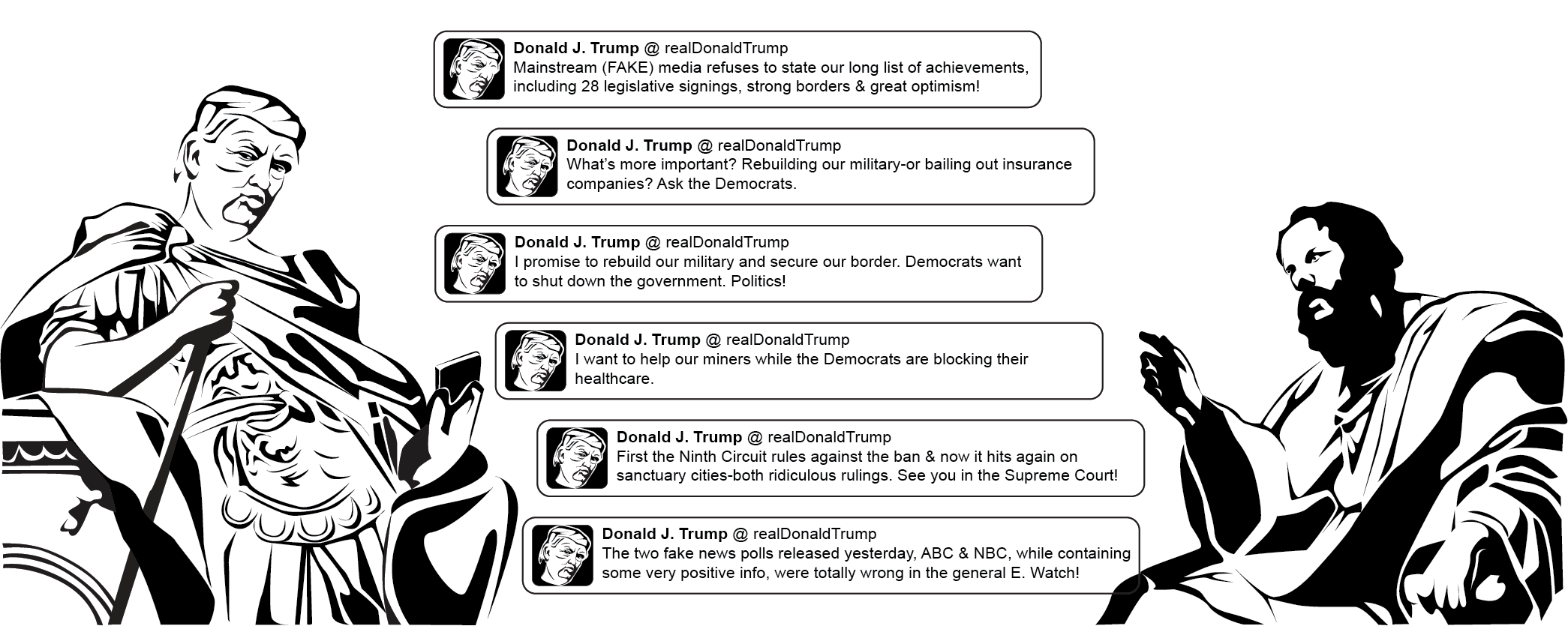

Donald Trump and Thucydidean Masculinity, One Year Later

Last year, in an article for Eidolon,

I suggested that both Trump and Alcibiades preyed upon their respective

voters’ insecurities, revealing that when masculinity is in crisis,

hypermasculine rhetoric will prevail, however irrational and

ill-informed the speaker. During the Republican primary discussions of

gender focused on Clinton, but the comparison allowed me — and hopefully

my audience — to consider how gender, specifically masculinity, shaped

Republican rhetoric.

Last year, in an article for Eidolon,

I suggested that both Trump and Alcibiades preyed upon their respective

voters’ insecurities, revealing that when masculinity is in crisis,

hypermasculine rhetoric will prevail, however irrational and

ill-informed the speaker. During the Republican primary discussions of

gender focused on Clinton, but the comparison allowed me — and hopefully

my audience — to consider how gender, specifically masculinity, shaped

Republican rhetoric.

In the time since, more and more attention was paid to Trump’s toxic masculinity, culminating in both a standoff between Republican primary candidates over hand (i.e. penis) size and the exposure of leaked audio where Trump casually discussed sexually assaulting women.

With Trump now president, his similarities with Alcibiades grow stronger. Given Trump’s insidious and fraught relationship with Russia (Alcibiades fled to Sparta, serving as an advisor in the war against Athens until the Spartans became suspicious of him; he then sought refuge with the Persians), his sex scandals (Alcibiades’ were innumerable — he even slept with the Spartan king’s wife), and our current constitutional crisis (some Athenians believed that Alcibiades was involved in an anti-democratic conspiracy, and he did, in fact, persuade the Athenians to adopt oligarchy), it’s tempting to imagine that my comparison was right. History is repeating itself.

Perhaps not: Neville Morley cautions that comparisons between the ancient and modern world too often ignore important differences that undermine any insights gained. In “Make Comparisons Great Again” and “How to Be a Good Classicist Under a Bad Emperor,” Donna Zuckerberg examines how the Alt-Right and men’s rights activists legitimize their platforms using images and texts from the ancient world. She cautions that we — as much as the Alt-Right and MRAs — need to be honest with ourselves and our audiences about our motives for making comparisons. Rather than letting the ancient texts speak for us, we need to both explain how the fundamental differences between past and present — those moments when comparisons fail — are precisely where a comparison’s usefulness lies.

Thucydides wrote that he would be content if his narrative is deemed useful

by those who will want to have a clear understanding of what happened — and, such is the human condition, will happen again at some time in the same or a similar pattern.

—The History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.22 (Tr. Hammond)

If this is the case—if the comparison’s salience means that we’re on course to repeat the mistakes of the past—then there’s little room or reason for hope. But we can’t afford to indulge in a past that renders us helpless or, worse, apathetic. No matter how similar, the past isn’t our future. Our story hasn’t been written. Resistance and hope lie in the differences rendered invisible by the similarities between Thucydides’ world and our own.

Before I complicate my comparison, however, I want to deepen it by showing the similarities between another Thucydidean figure, Pericles, and Obama. Obama’s farewell address, delivered on the eve of Trump’s inauguration, echoed sentiments of Pericles, the general who led the Athenians in the early years of the Peloponnesian War. Pericles’ expertise and restrained rhetoric was shaped by moderation and reason, qualities associated with pre-stasis masculinity in the Corcyra episode. Both Thucydides’ Pericles and Obama emphasize the importance of reason, facts, and deliberation as essential to citizen identity. Athenian confidence, Pericles says, comes from intelligence, and knowledge produces bold, calculating action and a more certain foresight. Similarly, Obama constructed science and reason as the foundation of American greatness, tempering and guiding bold action. Obama praised “the essential spirit of innovation and practical problem solving that guided our founders that allowed us to resist the lure of fascism and tyranny during the Great Depression.”

Some have suggested that Obama — his restraint, his commitment to reason and knowledge, his liberal, elite education — paved the way for populist leadership, a fate he appears to have shared with Pericles. As I noted in my previous article, preying upon voters insecurities — one of the hallmarks of hypermasculinity — led to unmitigated support for one of the greatest disasters of the war, the Sicilian Expedition. Thucydides notes that after Pericles’ death leaders in Athens “indulged popular whim, even in matters of state policy” (2.65; tr. Hammond), which led to communication failures, civil discord, and strife: in the aftermath of the Sicilian Debate the Athenians lodged personal accusations against one another in a bid for political power. Hypermasculinity — its lack of restraint and pandering for personal profit — breeds civil discord. If Obama is like Pericles and Trump like Alcibiades, will Athens’ future be our own?

The Thucydidean models of stasis and masculinity suggests that civil discord and conflict is coming; a rapidly crumbling Republican party, police violence, racial profiling, mass incarceration, and recent ICE raids suggest it’s already here. If Alcibiades and Trump really are comparable — if we are truly bound to repeat the mistakes of the past, human nature being what it is — is there any reason to hope? If not, is there any reason to resist?

I believe there is — but only if we recognize not just the power of our comparisons, but also their limits.

Thucydides shows us that hypermasculinity, left unchecked, threatens the integrity of productive deliberation and constitutional norms. Unrestrained by the norms of civil society, hypermasculine men espouse a rhetoric of patriotism that reflects the priorities of a single group, threatening successful deliberation by denying space for opposition. In Athens these young men, consumed by a passion for glory, silenced dissent. Trump’s supporters are predominantly white, middle to upper-middle class people lured by his promise to make America great again (that is, to make America white again).

But Thucydides’ observations of the human condition were based on individuals whose political agency was granted by virtue of their wealth, gender, and lineage: free, citizen men. Thucydides is helpful to the extent that hypermasculine norms and crises of masculinity still shape rhetoric. Thucydides can tell us how men behave, how voters are manipulated by patriotic rhetoric. But his belief that his history will be useful is predicated on the assumption that history will repeat itself precisely because the human condition — to anthropinon — is unchanging. Yet he recognizes the limits of his theoretical model: in his analysis of civil war in Corcyra he notes that the suffering observed in Corcyra will repeat itself so long as human nature remains the same.

If Thucydides resonates — if human nature seems unchanging — it’s because politics is still by and large the purview of those of gender, racial, or class privilege (and more often than not, all three). The fact that his history seems relevant today — that we see similar dynamics permeate politics — suggests that we still live in a Thucydidean world. Human nature only seems unchanging because politics continues to be dominated by the power of privileged men and those who agree to play by their rules. As long as we treat politics and the struggle for equality and social justice as a zero-sum game, electoral politics will continue to serve as an arena for men to distinguish themselves to the detriment of their constituents.

In my first article, I compared the conditions that led to the Athenians’ and our own crises of masculinity, focusing in particular on feminism. Feminism, however, is not the only story of masculinity’s crisis: ours is a crisis of white masculinity. When we gloss over these differences, we ignore important social factors that support Trump, such as racism.

Despite the passage of the 15th and 19th amendments, men of privilege still have more power — political, social, and institutional — than women and minorities. Republican gerrymandering, the “repeal the nineteenth” campaign, and the assault on voting rights all suggest that republicans perceive the diverse voices of the voting electorate as threatening. As Toni Morrison has noted, the election of a strong man reveals just how fragile whiteness really is. Roman and Greek history may feel more real than ever, but these can only be our stories if we deny the role racism and sexism have played in the election, if we reject the momentous strides that historically disenfranchised persons have taken in the struggle for equality, demanding equal access to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and the essential contribution these voices make to democratic discourse. To resist we must rigorously protect voting rights. Our diverse voting pool, after all, is what sets our electorate apart from the Athenians’.

Thucydides can tell us how men behave, how voters are manipulated by patriotic rhetoric. But he can’t tell us what the future holds, because human nature is not immutable. In fact, it’s not even “natural.” What we perceive as “human nature” or “natural differences” between people of different races, genders, and classes stem from structural inequalities. He can’t tell us what the future holds for a community of individuals whose experience of being American is both diverse and plural, who complicate the dominant hyperpatriotic rhetoric that seeks to silence dissent. Perhaps most importantly, Trump did not win the popular vote. Our path seems perilously similar to Athens, but only because the electoral college, which has always privileged the rural over the urban, determined the outcome of the election.

The current crisis of masculinity is as much shaped by feminism as it is by racism. When we ignore the differences between past and present, we erase important sites of resistance from our own narrative, as Rebecca Solnit reminds us. The past may have been written, but our future is not. We need new stories, not old ones. When we draw comparisons between the past and present without acknowledging the limits, we marginalize those for whom Thucydides was never and will never be a touchstone. When we don’t address this, we run the risk of overlooking how race, gender, and class shape our own politics, thereby normalizing and naturalizing the differences that these categories instill.

This is why intersectional feminism is more important now than ever, and why we, as classicists, should recognize this. Most of the canonical texts of the classical world were written by the privileged. Our understanding of life for the silenced of Greece and Rome — the enslaved, the poor, women, children — is filtered through an elite perspective. We look to these texts to help us understand the experience of being Roman or Greek, but we also recognize how limited our scope is.

But we have no excuse to let our own politics be shaped by an equally narrow worldview. Our access to diverse perspectives from antiquity is limited, but this is not true of today’s world. Understanding how oppression comes in many forms — how it is intersectional — will make us not only better citizens, but also better teachers. A black woman’s and white woman’s experience of oppression is not going to be the same, nor a gay man’s the same as a trans person of color’s. Our concerns as Americans, therefore, are going to be diverse, and we must have compassion for the very real suffering of others. But first we have to listen.

Understanding how oppression is intersectional and diverse is also an opportunity to consider how the experience of reading texts, like Aristotle’s discussion of slavery in The Politics or the rape of Pamphila in Terence’s Eunuch, is not going to be the same for every student. Power and privilege shape Aristotle’s construction of nature and how characters in The Eunuch respond to rape. Acknowledging this and critically examining how inequality is normalized offers an opportunity to engage students who might otherwise see the classics as reifying the very categories of oppression that shape their own lives.

Rather than looking for precedent, we must critically engage with the mistakes of the past, highlight the differences, and build a more inclusive future. In doing so, we may save not only ourselves but also our discipline.

Jessica Evans is lecturer of Classics at the University of Vermont.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου