Η ΜΟΥΣΙΚΗ ΣΤΑ ΝΑΖΙΣΤΙΚΑ ΣΤΡΑΤΟΠΕΔΑ ΣΥΓΚΕΝΤΡΩΣΗΣ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1933 ΕΩΣ ΤΟ 1945 (αναλυτικός οδηγός)

Music in Concentration Camps 1933-1945

Fackler, Guido

It would be wrong to reduce the “Music of the Shoah” (Holocaust/churbn)

to the Yiddish songs from the ghetto camps of Eastern Europe or to the

multiple activities in the realm of classical or Jewish music found in

the ghetto camp at Theresienstadt (Terezín), which of course enjoyed a

special status as a model camp. It would be equally wrong to restrict

our view of music in concentration camps to the “Moorsoldatenlied” (“The

Peat Bog Soldiers”), the “Buchenwald Song,” the “Dachau Song,” or the

so-called “Girls’ Orchestra in Auschwitz,” described by Fania Fénelon –

also the subject of the Hollywood film entitled “Playing for Time”.[1] Instead of this, I wish to address the topic of musical activities in general in the concentration camps.[2]

Thus this chapter is about those camps that the Nazi regime started to

erect just a few weeks after Hitler’s assumption of power; these camps

formed the seed from which the entire system of Nazi camps grew, and

which eventually consisted of over 10,000 camps of various kinds.[3]

In fact music was an integral part of camp life in almost all the Nazi-run camps. The questions covered by my research include: how was it possible to play music in these camps? What musical forms developed there? What, under these circumstances was the function, the effect and the significance of music for both the suffering inmates and the guards who inflicted the suffering? And how was the extent of musical activities affected by the development of the concentration camp system? My research is based on extensive archive work, the study of memoirs and literature, and interviews with witnesses. In the first part of this essay I describe the various forms of music performed at the behest of the SS in the camps. In the second part I analyze the very different question of the musical activities initiated by the inmates themselves.

In fact, under these extreme conditions, being forced to sing could be life-threatening. Prisoners who did not immediately obey the order, “In step ... March! Sing!,”[5] or who did not carry out the order, “Sing, a Song!”[6] to the complete satisfaction of the SS provided an occasion for random beatings, as reported by Eberhard Schmidt from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp: “Anyone who did not know the song was beaten. Anyone who sang too softly was beaten. Anyone who sang too loud was beaten. The SS men lashed out wildly”.[7] Karl Röder, who had been a prisoner in Dachau and Flossenbürg, wrote that singing songs on command was part of the daily routine of camp life: “We sang in small groups, or one block would sing, or several thousand prisoners all at once. In the latter case, one of us had to conduct because otherwise it would not have been possible to keep time. Keeping time was very important: it had to be crisp, military, and above all loud. After several hours’ singing we were often unable to produce another note”. [8]

Command singing took place on several occasions; while marching, while doing exercises, during roll-call, and on the way to or from work. Frequently, singing was compulsory even during forced labor. It was by no means unusual for singing to provide the macabre background music for punishments, which were stage-managed as a deterrent, or even as a means of sadistic humiliation and torture. Joseph Drexel in the Mauthausen concentration camp for instance, was forced to give a rendering of the church hymn ”O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” (“Jesus’ blood and wounds”)[9] while being flogged to the point of unconsciousness. Punishment beatings over the notorious flogging horse (the “Bock”) were performed accompanied by singing, and the same is true of executions.

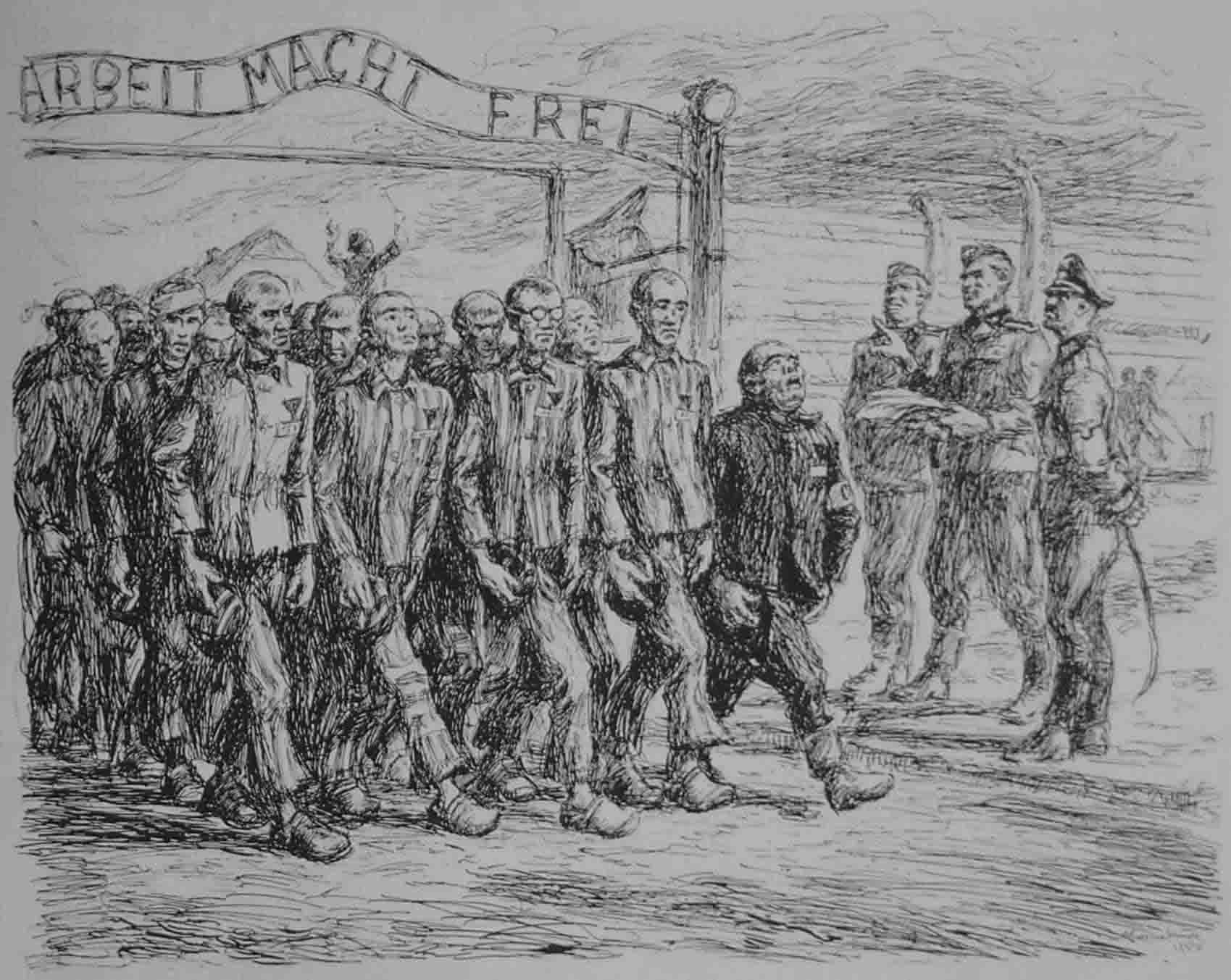

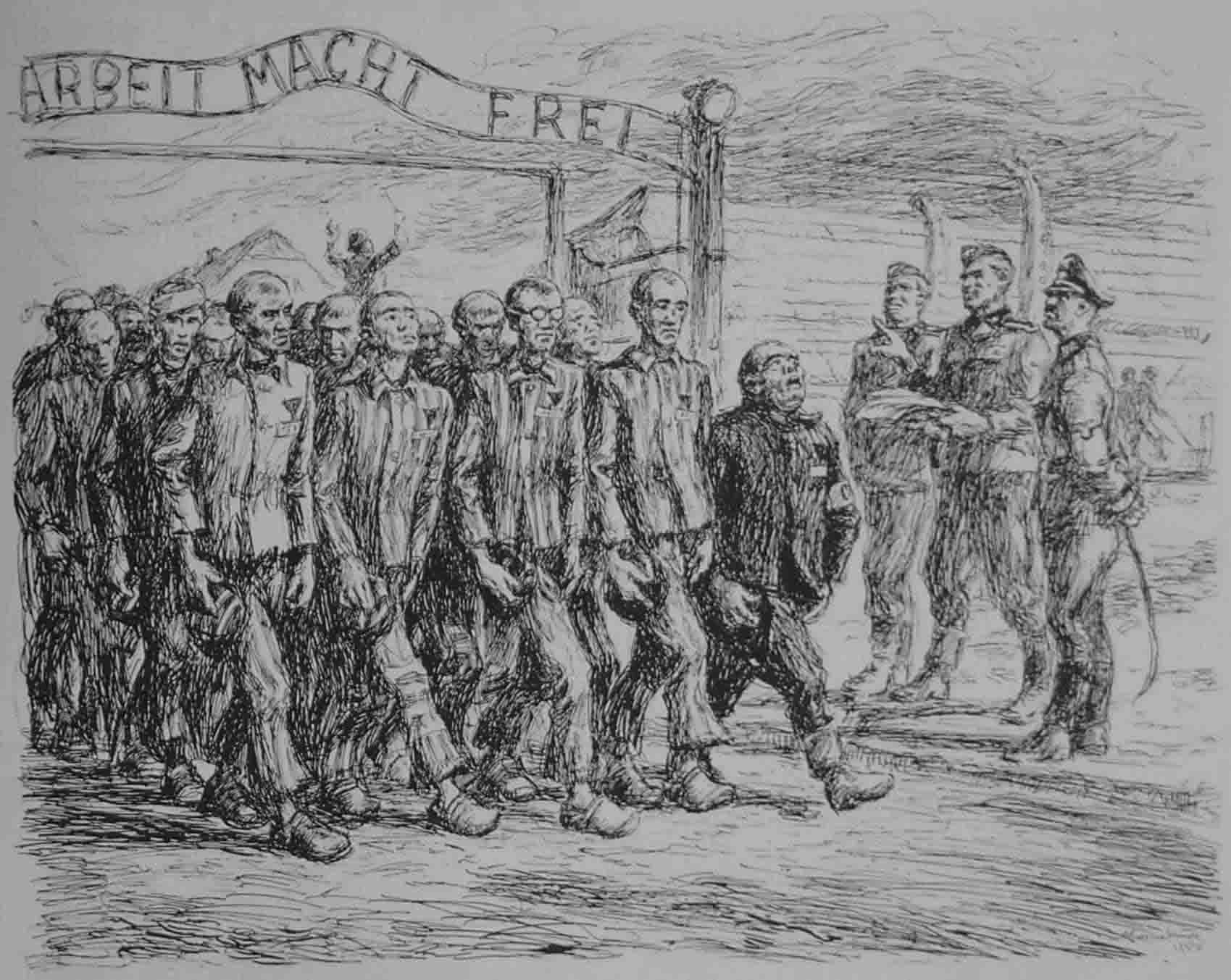

Figure 1. This pen-and-ink drawing under the title “Wymarsz komand do praxy” (“Marching to work”), from the cycle “Day of the prisoner” (1950), was made by Mieczysław Koscielniak, a former prisoner, in 1950. It shows a work detail leaving Auschwitz: in the background a prisoner can be seen conducting the camp orchestra (published in M. Koscielniak: Bilder von Auschwitz, 2d ed. (Frankfurt a. M., 1986, n.p.)

The demoralizing effect of being forced to sing resulted not just

from the situations in which the prisoners were forced to sing, but also

from the deliberate choice of certain songs. While the guards and

officials did not usually prescribe any particular song, the prisoners

generally chose pieces which were not calculated to unnecessarily

provoke the guards. German folk songs with banal, countrified or naive

texts, were particularly popular with the SS and were repeated to the

point of stupefaction. These songs, of course, formed a harsh contrast

with the hopeless situation of the prisoners. According to Eugen Kogon,

who was imprisoned in the Buchenwald camp, a degree of “stoicism and

callousness”[10] was

necessary in order to endure such songs as “Hoch auf dem gelben Wagen”

(“Up there on the yellow wagon”) or “Auf den Bergen so hoch da droben

steht ein Schloß” (“High on the mountains yonder stands a castle”),[11] or the sentimental ballad “Hüttlein am Waldesrand” (“Little hut on the edge of the forest”)[12]

while faced with the daily terror of life in the camps. When the guards

ordered the prisoners to sing such Nazi songs as the

“Horst-Wessel-Lied” (“Horst-Wessel-Song”), or military or patriotic

songs, this confronted the prisoners with the contrast between the

National Socialist view of life and their own hopeless situation.

Alternatively, the prisoners might be ordered to sing songs with

double-meanings, or obscene or salacious texts, offending the prisoners’

sense of shame. Certain groups of prisoners were deliberately

humiliated by being forced to sing songs of particular significance to

that group; and the guards showed “an astonishing awareness of how to

outrage people by breaking taboos and abusing symbols”.[13]

Communists and Social Democrats, for instance, were forced to sing

songs from the workers’ movement, while the faithful were forced to sing

their religious songs.

The guards forced prisoners to sing not just well-known songs, but also songs which originated in the camps. These so-called concentration camp songs were either newly composed or else variations on existing songs. Thus, “Wir sind die Sänger von Finsterwald” (“We are the Darkwood Singers”) became “Wir sind die Sänger von Buchenwald” (“We are the Buchenwald – Beechwood – Singers”).[14] Other camp songs were specially commissioned by the SS, including the anti-Semitic “Judenlied” (“Jews’ Song”), which was composed by a prisoner in Buchenwald who had been assessed as ‘asocial.’ The song begins: “Jahrhundert’ haben wir das Volk betrogen, / kein Schwindel war uns je zu groß und stark, / wir haben geschoben nur, gelogen und betrogen, / sei’s mit der Krone oder mit der Mark“ (“For hundreds of years we cheated the people, / no swindle was too outrageous / we wangled, we lied, we cheated, we narked / whatever the currency, the crown or the mark”).[15]

Besides these songs, many concentration camps had their own special anthem which served as a sort of official signature tune for the camp. The model for all these concentration camp anthems (KZ-Hymnen) was composed in the summer of 1933 in the Börgermoor concentration camp near Papenburg. This is the “Börgermoorlied” (“Song of Börgermoor”), but it is better know under the title “Moorsoldatenlied” (also “Die Moorsoldaten” or “Lied der Moorsoldaten,” English: “The Peat Bog Soldiers” or “The Peat Bog Soldiers’ Song”).[16] This song was not the brainchild of the SS: in fact it was repeatedly prohibited. Nevertheless it spread throughout the camp system as prisoners were transferred to other camps. In this way it became the most popular of all concentration camp songs, symbolizing for the inmates both protest and determined endurance.

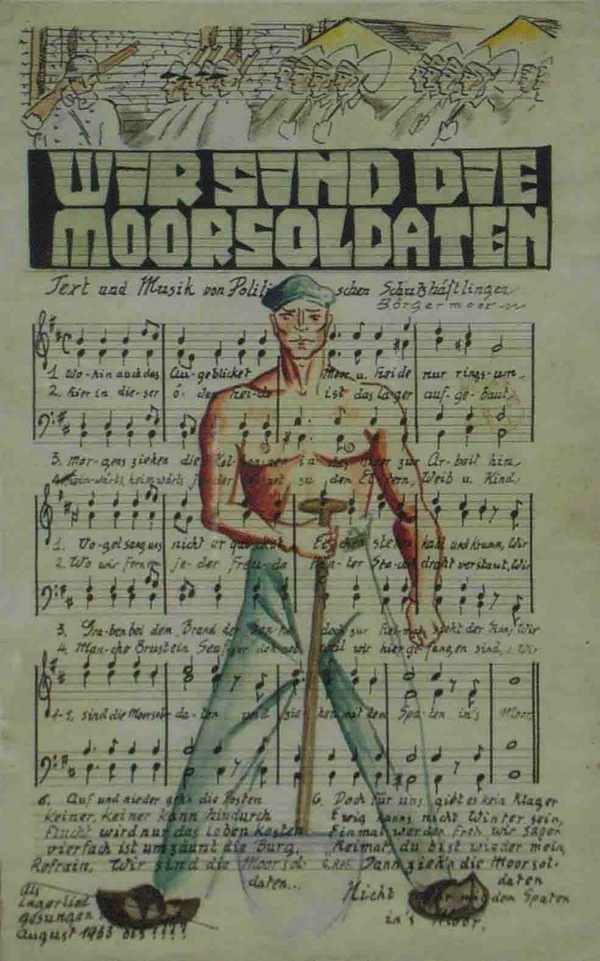

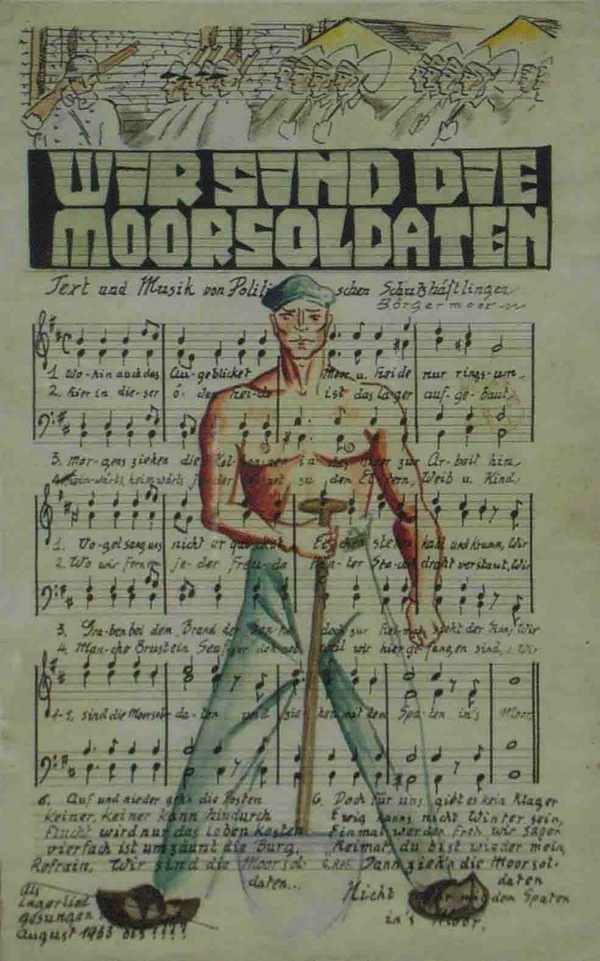

Figure 2. A copy of the “The Peat Bog Soldiers” made by Hanns Kralik in the KZ Börgermoor 1933. After his release Günter Daus brought this copy outside the camp. Archive of Dokumentations- und Informationszentrum Emslandlager (Documentation and Information Center Emslandlager) in Papenburg, Germany, estate Günter Daus.

The text of another concentration camp anthem, the “Treblinkalied” (“Treblinka Song”),[17] is probably the work of a member of the SS, Kurt Hubert Franz, while the tune is that of the “Buchenwaldlied” (“Buchenwald Song”, lyrics: Fritz Löhner-Beda, music: Hermann Leopoldi), [18] written in December 1938 on order of the camp commander. The commander in the KZ Sachsenhausen also ordered a camp anthem to be written, and this resulted in winter 1936/37 in the “Sachsenhausenlied” (“Sachsenhausen Song”).[19]

In fact music was an integral part of camp life in almost all the Nazi-run camps. The questions covered by my research include: how was it possible to play music in these camps? What musical forms developed there? What, under these circumstances was the function, the effect and the significance of music for both the suffering inmates and the guards who inflicted the suffering? And how was the extent of musical activities affected by the development of the concentration camp system? My research is based on extensive archive work, the study of memoirs and literature, and interviews with witnesses. In the first part of this essay I describe the various forms of music performed at the behest of the SS in the camps. In the second part I analyze the very different question of the musical activities initiated by the inmates themselves.

I. Music on Command

Almost every camp inmate was inescapably confronted in one way or another with music in the course of his or her camp imprisonment. This took place mainly within the officially prescribed framework of daily life in the camps: singing was required and there were camp orchestras; but music was also played over loudspeakers. Besides these occasions, camp inmates were forced to perform music for the SS “after hours,” as it were.Singing on Command

Once the camp system had been developed, the most common form of command music in the concentration camps was singing on command.[4] The inmates received the order to strike up a song from a sentry, for example, or from a prisoner functionary (the latter were prisoners to whom the SS had delegated such special organizational and administrative tasks as leading a work detail or supervising a block: for example, a Kapo). This form of collective music derives from military tradition, where even today singing is used to develop discipline, encourage marching rhythm, or to symbolize the acquisition of such soldierly virtues as “proper order”. The practice was employed in concentration camps, however, with the additional purpose of exercising mental and physical force. The guards used singing on command to intimidate insecure prisoners: it frightened, humiliated, and degraded them. After a long day of hard manual work, being forced to sing meant an enormous physical effort for the weakened prisoners.In fact, under these extreme conditions, being forced to sing could be life-threatening. Prisoners who did not immediately obey the order, “In step ... March! Sing!,”[5] or who did not carry out the order, “Sing, a Song!”[6] to the complete satisfaction of the SS provided an occasion for random beatings, as reported by Eberhard Schmidt from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp: “Anyone who did not know the song was beaten. Anyone who sang too softly was beaten. Anyone who sang too loud was beaten. The SS men lashed out wildly”.[7] Karl Röder, who had been a prisoner in Dachau and Flossenbürg, wrote that singing songs on command was part of the daily routine of camp life: “We sang in small groups, or one block would sing, or several thousand prisoners all at once. In the latter case, one of us had to conduct because otherwise it would not have been possible to keep time. Keeping time was very important: it had to be crisp, military, and above all loud. After several hours’ singing we were often unable to produce another note”. [8]

Command singing took place on several occasions; while marching, while doing exercises, during roll-call, and on the way to or from work. Frequently, singing was compulsory even during forced labor. It was by no means unusual for singing to provide the macabre background music for punishments, which were stage-managed as a deterrent, or even as a means of sadistic humiliation and torture. Joseph Drexel in the Mauthausen concentration camp for instance, was forced to give a rendering of the church hymn ”O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” (“Jesus’ blood and wounds”)[9] while being flogged to the point of unconsciousness. Punishment beatings over the notorious flogging horse (the “Bock”) were performed accompanied by singing, and the same is true of executions.

Figure 1. This pen-and-ink drawing under the title “Wymarsz komand do praxy” (“Marching to work”), from the cycle “Day of the prisoner” (1950), was made by Mieczysław Koscielniak, a former prisoner, in 1950. It shows a work detail leaving Auschwitz: in the background a prisoner can be seen conducting the camp orchestra (published in M. Koscielniak: Bilder von Auschwitz, 2d ed. (Frankfurt a. M., 1986, n.p.)

The guards forced prisoners to sing not just well-known songs, but also songs which originated in the camps. These so-called concentration camp songs were either newly composed or else variations on existing songs. Thus, “Wir sind die Sänger von Finsterwald” (“We are the Darkwood Singers”) became “Wir sind die Sänger von Buchenwald” (“We are the Buchenwald – Beechwood – Singers”).[14] Other camp songs were specially commissioned by the SS, including the anti-Semitic “Judenlied” (“Jews’ Song”), which was composed by a prisoner in Buchenwald who had been assessed as ‘asocial.’ The song begins: “Jahrhundert’ haben wir das Volk betrogen, / kein Schwindel war uns je zu groß und stark, / wir haben geschoben nur, gelogen und betrogen, / sei’s mit der Krone oder mit der Mark“ (“For hundreds of years we cheated the people, / no swindle was too outrageous / we wangled, we lied, we cheated, we narked / whatever the currency, the crown or the mark”).[15]

Besides these songs, many concentration camps had their own special anthem which served as a sort of official signature tune for the camp. The model for all these concentration camp anthems (KZ-Hymnen) was composed in the summer of 1933 in the Börgermoor concentration camp near Papenburg. This is the “Börgermoorlied” (“Song of Börgermoor”), but it is better know under the title “Moorsoldatenlied” (also “Die Moorsoldaten” or “Lied der Moorsoldaten,” English: “The Peat Bog Soldiers” or “The Peat Bog Soldiers’ Song”).[16] This song was not the brainchild of the SS: in fact it was repeatedly prohibited. Nevertheless it spread throughout the camp system as prisoners were transferred to other camps. In this way it became the most popular of all concentration camp songs, symbolizing for the inmates both protest and determined endurance.

Figure 2. A copy of the “The Peat Bog Soldiers” made by Hanns Kralik in the KZ Börgermoor 1933. After his release Günter Daus brought this copy outside the camp. Archive of Dokumentations- und Informationszentrum Emslandlager (Documentation and Information Center Emslandlager) in Papenburg, Germany, estate Günter Daus.

The text of another concentration camp anthem, the “Treblinkalied” (“Treblinka Song”),[17] is probably the work of a member of the SS, Kurt Hubert Franz, while the tune is that of the “Buchenwaldlied” (“Buchenwald Song”, lyrics: Fritz Löhner-Beda, music: Hermann Leopoldi), [18] written in December 1938 on order of the camp commander. The commander in the KZ Sachsenhausen also ordered a camp anthem to be written, and this resulted in winter 1936/37 in the “Sachsenhausenlied” (“Sachsenhausen Song”).[19]

Music in Concentration Camps 1933-1945

TΟ ΘΡΥΛΙΚΟ ΤΡΑΓΟΥΔΙ ΑΝΤΙΣΤΑΣΗΣ ΤΩΝ ΚΡΑΤΟΥΜΕΝΩΝ

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου