No one can deny the artistic genius of Dutch Post-Impressionist artist

Vincent van Gogh,

whose masterworks are among the most famous and easily recognizable

paintings in the world. Nevertheless, the artist’s reputation remains

inextricably tied to his struggles with mental illness—this is, after

all, the man who

cut off his left ear and

gifted it to a female acquaintance.

It was that

infamously violent incident in Arles, France, on

December 23, 1888, that

led Van Gogh to Saint-Paul-De-Mausole, an asylum in

Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France. He lived there for just over a year,

from May 8, 1889, to May 16, 1890. In the new book

Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum,

journalist and Van Gogh scholar Martin Bailey delves into this critical

and remarkably fruitful period in the artist’s career. The author

brings to light new details about what life at Saint-Paul was like, the

paintings Van Gogh created while he was there, as well as insight into

the artist’s fragile mental state, and a fascinating account of the

staff and the other patients.

To illuminate this history, Bailey’s gorgeously illustrated tome

draws on primary sources, including Van Gogh’s letters, an unpublished

diary from a local artist who knew Van Gogh at the time, and rarely

consulted records from the municipal archives of Saint-Rémy, of

Saint-Paul’s admission register from the late 19th century.

The author also considers the history of the facility, which was

founded by Louis Mercurin as an impressively progressive institution

that embraced music and art as forms of therapy. The asylum was given a

failing grade by inspectors in 1874 and was in dire need of reform prior

to Van Gogh’s arrival. Though conditions during the artist’s

institutionalization still left room for improvement, Van Gogh became

close with the director, Théophile Peyron, and maintained the freedom to

work (save for the nadir of his mental crises).

The institutionalization was voluntary, and unlike many asylums of

the time, Saint-Paul eschewed the use of straight jackets, refusing to

chain up its patients or employ other cruel practices. Nevertheless,

mental illness was still poorly understood at the time, and

institutionalization must have been difficult for Van Gogh.

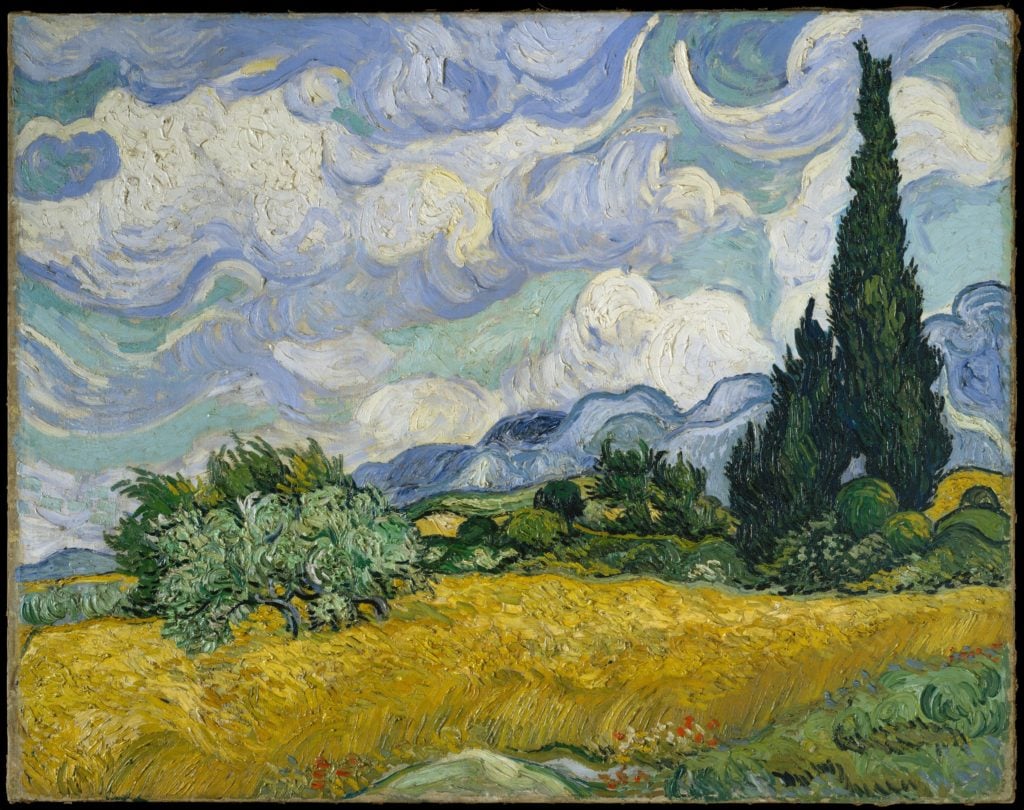

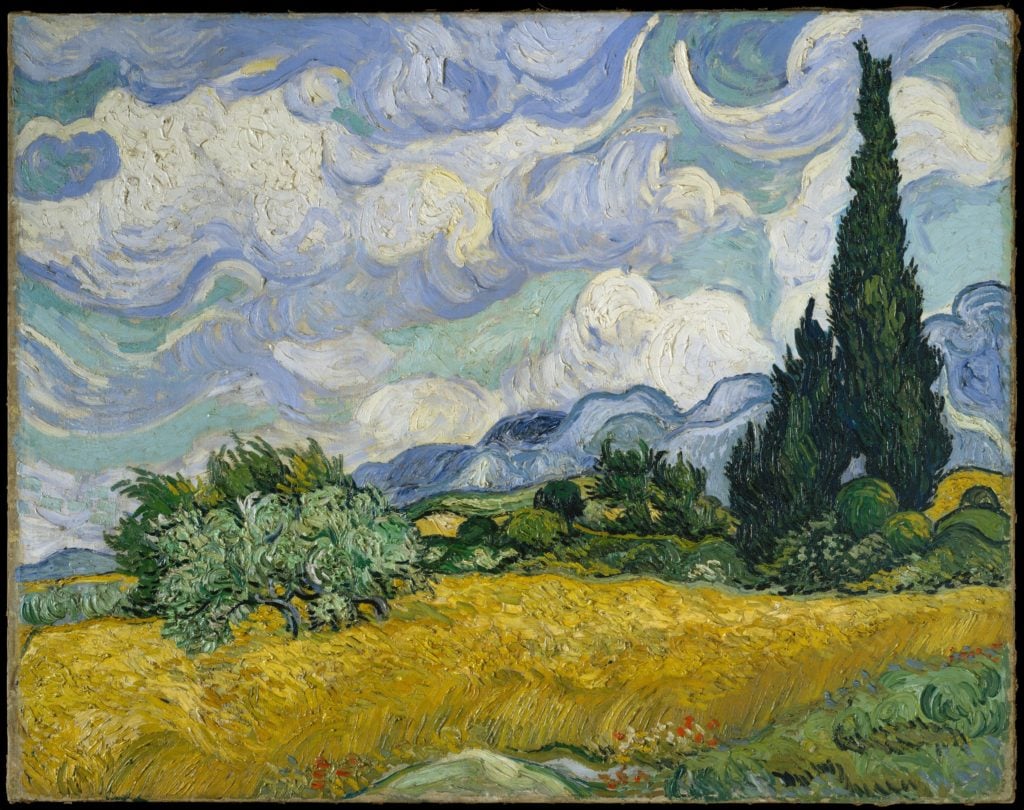

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield With Cypresses (1889). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The artist, lucid for the majority of his stay, was surrounded by men

who were much worse off, according to the book. There was an elderly

priest, likely suffering from dementia, a nonverbal “idiot” with a

mental age of less than three who lived at Saint-Paul for nearly 45

years, and a man who Van Gogh complained in a letter “breaks everything

and shouts day and night.” (Bailey has identified many of these men by

name for the first time.)

Nevertheless, Van Gogh came to identify with his fellow patients, who

he called “my companions in misfortune.” He also continued to struggle,

suffering through four severe mental health episodes while he was

there. During these periods, Van Gogh would poison himself by eating his

paints, and then become paranoid, convinced that someone else was

making an attempt on his life. “My memories of these bad moments are

vague,” he wrote to his brother, Theo van Gogh, admitting to eating

“filthy things.”

“Strictly speaking I’m not mad, for my thoughts are absolutely normal

and clear between times…. but during the crises it’s terrible however,

and then I lose consciousness of everything,” Van Gogh explained, noting

in another missive that “it’s to be presumed that these crises will

recur in the future, it is ABOMINABLE.”

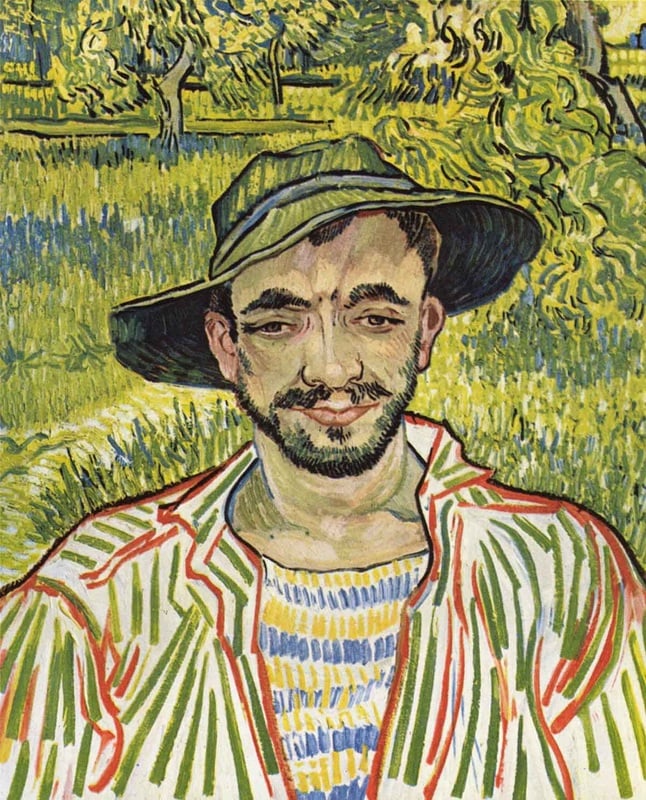

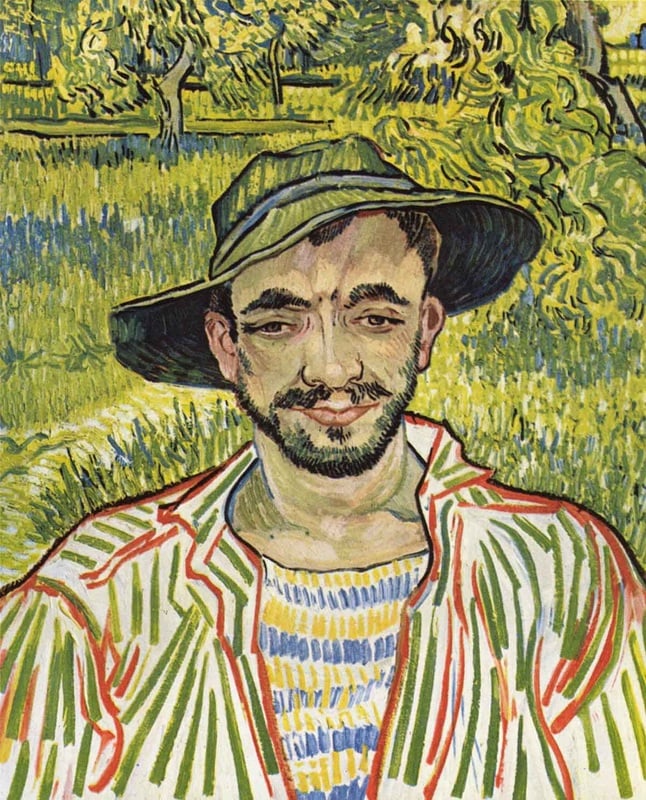

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of a Gardener (1889), now identified as Jean Barral. Courtesy of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome.

There has been endless speculation over the years as to the

true nature of the mysterious mental illness

that plagued Van Gogh. Like others before him, Bailey speculates might

have been bipolar disorder. Whatever the true diagnosis, toward the end

of his stay at Saint-Paul, Van Gogh came to feel that being surrounded

by the mentally ill made his own issues worse.

In between episodes—and occasionally during them—Van Gogh made great

paintings, over 150 of which survive. From his bedroom window, the

artist enjoyed views of golden wheatfields, which he painted throughout

the year. Beyond lay the equally inspiring olive groves, and the hills

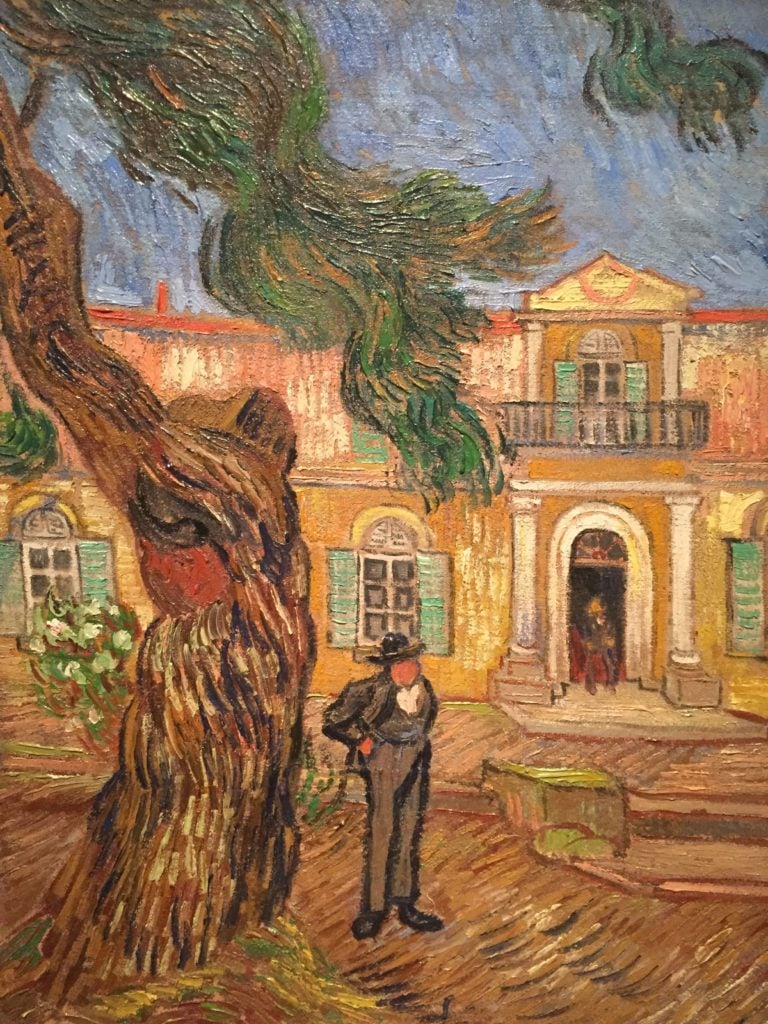

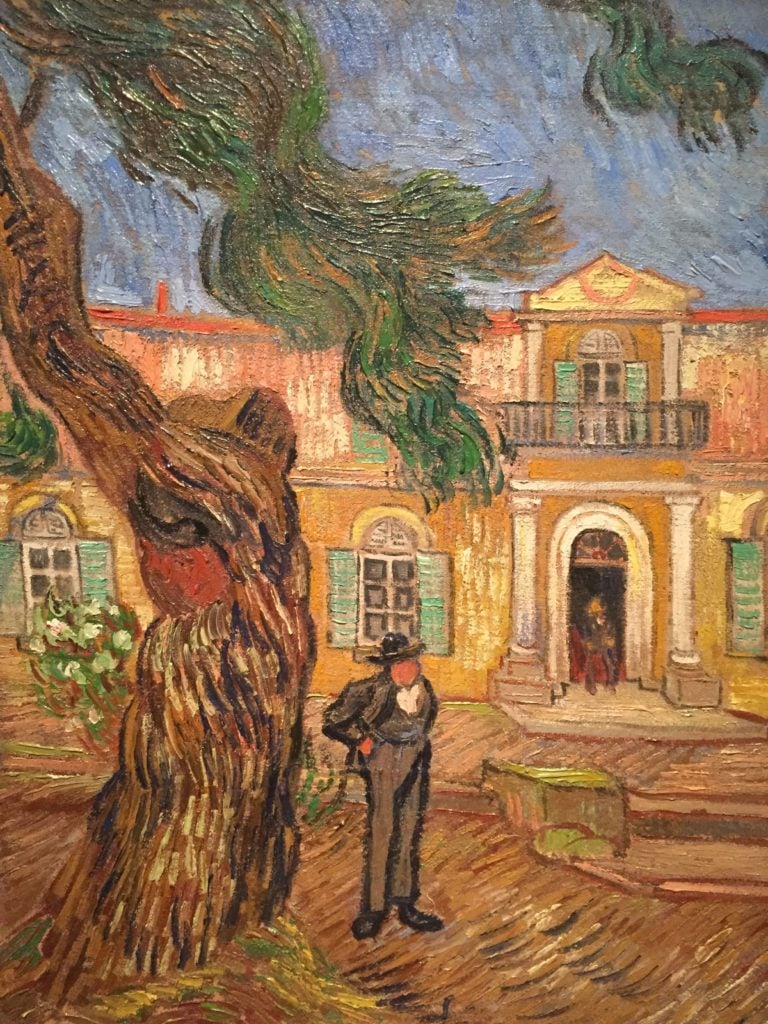

of Les Alpilles. Saint-Paul itself was also a common subject for the

artist, who spent many hours in its beautiful, if somewhat overgrown,

walled garden, and occasionally depicted the facility’s rooms. (Only one

piece, which we’ll get to later, featured the building’s exterior.)

Unsurprisingly, given his productivity, Van Gogh wasted not a minute

upon arriving at Saint-Paul. The very next day, he was at work on two

flower paintings, including

Irises, now in the collection of Los

Angeles’s J. Paul Getty Museum. It took just two weeks to almost

completely exhaust the art supplies he had brought with him from Arles.

Vincent van Gogh, Irises (1889). Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Other works completed at Saint-Paul include self-portraits and portraits of the staff. Bailey identifies

Portrait of a Gardener

(1889) as farmer Jean Barral, a conclusion based on the work of a local

researcher who, in the 1980s, spoke to the grandson of an asylum

orderly—and even two of Van Gogh’s fellow patients. Van Gogh also

created oil paintings based on black and white copies of the work of

other artists, including

Eugène Delacroix’s

Pietà and Jean-François Millet’s series “Labours of the Fields.”

Although institutionalization did not cure what ailed Van Gogh, the

artist’s time at Saint-Paul led to the creation of some of his most

beloved works.

Here are 11 things we learned about Van Gogh from Bailey’s new book.

1. You Can Visit Van Gogh’s Asylum Today (But Don’t Expect to See His Work)

Formerly a monastery, Saint-Paul-De-Mausole has become something of a

tourist attraction, less for the charms of its Romanesque architecture

than for its links to Van Gogh. The facility remains a psychiatric

hospital today, but the public can visit the gardens, the chapel, and

12th-century cloister, as well as several rooms, including one furnished

as if it were 1889 again. The sign reads “Van Gogh’s Bedroom,” but the

artist actually slept in a different part of the asylum.

Back in 1987, Bailey had the rare opportunity to visit what was once

the men’s block, since modernized, where Van Gogh would have lived

during his institutionalization. According to the author, the hospital,

inundated by similar requests as the centenary of the artist’s death

approached, soon cracked down on such access, which is now all-but

unheard of. (The book includes photographs taken by Bailey in this

off-limits area, the first such images ever published in color.)

Before booking a visit, note that the hospital does not own any work

by Van Gogh. The artist offered to donate some paintings to the Catholic

Sisters of the Order of Saint Joseph, who ran the facility, but they

found his work disturbing and turned him down. Since Van Gogh checked

out in 1890, his work has only once been exhibited in the town of

Saint-Rémy, back in 1951.

Vincent van Gogh, View of the Asylum With a Pine Tree (1889). Courtesy of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

[............................]

Συνεχίστε την ανάγνωση

Μαρία Ζιάκα

Μαρία Ζιάκα

Ο Σύλλογος Αποφοίτων Φιλοσοφικής Α.Π.Θ. «Φιλόλογος» σε συνεργασία με

το Εργαστήριο για τη Μελέτη της Ανάγνωσης και της Γραφής στην Εκπαίδευση

και στην Κοινωνία του Παιδαγωγικού Τμήματος Δημοτικής Εκπαίδευσης του

Α.Π.Θ. (Ε.Μ.Α.Γ.Ε.Κ.), το Πανελλήνιο Δίκτυο για το Θέατρο στην

Εκπαίδευση, και το 1ο Γυμνάσιο Καλαμαριάς οργανώνει επιμορφωτικό

σεμινάριο διάρκειας δώδεκα (12) ωρών με θέμα: «Σχολική Λέσχη Ανάγνωσης:

Βασικές αρχές οργάνωσης και λειτουργίας».

Ο Σύλλογος Αποφοίτων Φιλοσοφικής Α.Π.Θ. «Φιλόλογος» σε συνεργασία με

το Εργαστήριο για τη Μελέτη της Ανάγνωσης και της Γραφής στην Εκπαίδευση

και στην Κοινωνία του Παιδαγωγικού Τμήματος Δημοτικής Εκπαίδευσης του

Α.Π.Θ. (Ε.Μ.Α.Γ.Ε.Κ.), το Πανελλήνιο Δίκτυο για το Θέατρο στην

Εκπαίδευση, και το 1ο Γυμνάσιο Καλαμαριάς οργανώνει επιμορφωτικό

σεμινάριο διάρκειας δώδεκα (12) ωρών με θέμα: «Σχολική Λέσχη Ανάγνωσης:

Βασικές αρχές οργάνωσης και λειτουργίας».