Letter Writing In The Ancient World

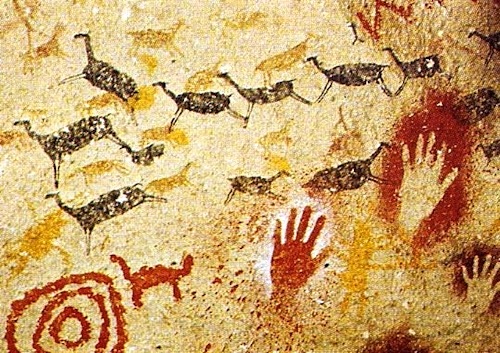

Since

the beginning of man, people have always wanted to communicate. And they

wanted to communicate important things in their lives. The prehistoric

cave drawings in Altimira in Spain and Lascaux in France cry out the

lives and the being of those extremely remote people. The hands on the

walls say, “I did this drawing. I was here. I existed. And I managed to

survive by my wit, my mind, by hunting and killing animals many times my

size. And this is how I did it. And I express how I did it through

communicating the important things in my life with my hands.”

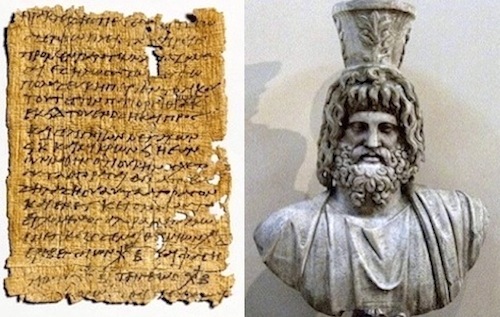

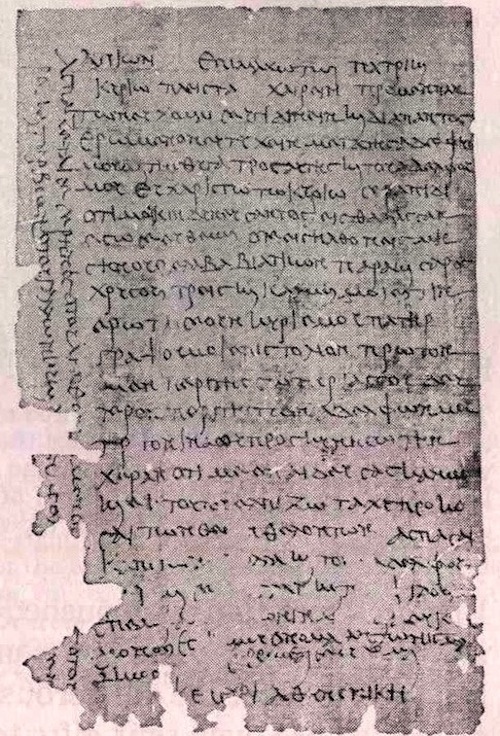

Thousands of years after prehistoric

cave men, people were still communicating through their hands the

important events in their lives through letters written on papyrus

rather than through drawings on cave walls. By the Greco-Roman times,

there was a formula for letter writing taught in all Greek and Roman

schools. It began with an introduction of the writer and the identity

of the recipient. There was a short greeting and often a thanksgiving

for health or safety. The author then presented the main body of the

letter and would conclude with wishes for good health and a farewell.

Here’s a potpourri of letters written by people in the first to third

centuries of the Christian faith:

Hilarion was the husband of pregnant

Alis and had apparently gone to Alexandria where there was work and he

would be able to send some money home. Obviously the child he mentions

was a boy of theirs. He tells her to kill or abandon on the garbage a

girl if she has one, but to keep the male child. Abortion and newborn

abandonment were common in the ancient pagan world. Alis worried that

Hilarion would “forget her” in Alexandria and he reassures her he won’t.

The god

Serapis was created by Ptolemy I, a Greek ruler of Egypt, in the 3rd

century BC in order to unite both the Egyptians and the Greeks. Serapis

had a human head rather than the typical Egyptian animal head because

Greeks always gave their gods human forms. The mother is named Serapis

like the god and invokes that god to keep her children healthy. She is a

loving mother who is beside herself with joy when a letter arrives from

her children, as was their nurse and their tutor.

This rather unloving and chiding letter

from older sisters to their two younger sisters is a universal one of

older siblings lording it over the younger ones: light the lamp in the

shrine to the gods; shake the dust off all the cushions; keep studying;

don’t worry about Mother; don’t play in the courtyard where people will

see your offensive behavior; behave yourselves when you are outside the

house; take care of Titoas and Spharus (maybe dogs?). And not even a

Farewell!

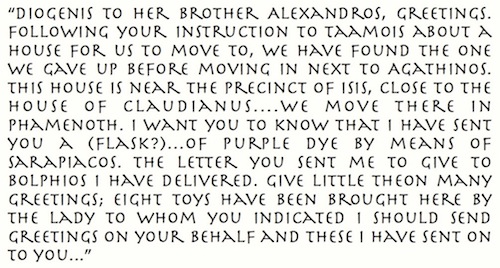

Diogenis’

brother Aurelius had instructed (his friend?) Taamois to find a house

for his sister and family. They had apparently settled on a house at one

time but instead they had moved next to Agathinos. Now they have bought

the original house that is near the precinct of Isis (a goddess and her

temple) and close to Claudianus’ home. They will move into the house in

the winter month of Phamenoth. Diogenis wants her brother to know that

Serapiacos should have delivered the purple dye she sent him. And she

delivered to Bolphios the letter he sent her to give to him. “Little

Theon” is probably her brother’s child, Diogenis’ nephew, and she is

pleased to say the eight toys for Theon have arrived at their home and

she is sending them to him with this letter. This is a real estate and

“things” (purple dye, toys) letter from a sister to her brother who are

both well-off enough to buy houses and things.

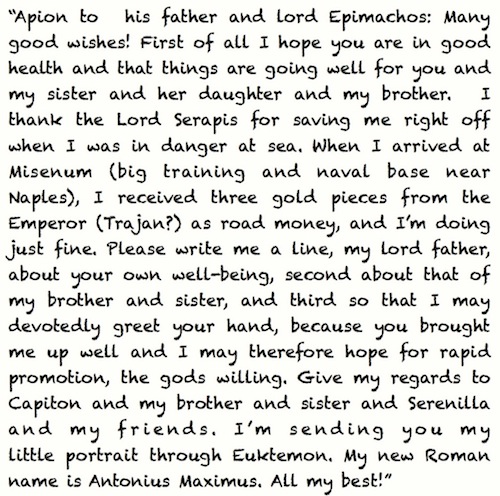

Letter

home to his father Epimachos from a young recruit named Apion from

Egypt who had enlisted in the Roman Army in the 2nd century AD.

Because the letter has no mention of his

mother, she was probably dead. Apion enlisted in the Roman army at

Alexandria, got on a big Roman government ship filled with Egyptian

recruits and sailed to Italy. The ship made it through a terrible storm

and arrived at Misenum where he was to be trained. Apion received three

gold pieces to tide him over and to get to his base once he was trained.

He thanks his father for bringing him up well and giving him the

education that will enable him to move up the military ranks. There

were obviously portrait-painters employed by the Roman army who would

for a fee paint a papyrus picture of the new recruit to send back home

to his family. His friend Euktemon is going to deliver the letter to

Apion’s family and give them the portrait of their Roman army son. And

he proudly tells his father his new Roman name that would replace his

Greek name, as was the custom in the Roman army. But you rarely hear the

words, “I love you,” in ancient Greco-Roman writings or, for that

matter, in some cultures on our planet today.—Sandra Sweeny Silver

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου